Protecting the wellbeing of our users

People use AI for a wide variety of reasons, and for some that may include emotional support. Our Safeguards team leads our efforts to ensure that Claude handles these conversations appropriately—responding with empathy, being honest about its limitations as an AI, and being considerate of our users' wellbeing. When chatbots handle these questions without the appropriate safeguards in place, the stakes can be significant.

In this post, we outline the measures we’ve taken to date, and how well Claude currently performs on a range of evaluations. We focus on two areas: how Claude handles conversations about suicide and self-harm, and how we’ve reduced “sycophancy”—the tendency of some AI models to tell users what they want to hear, rather than what is true and helpful. We also address Claude’s 18+ age requirement.

Suicide and self-harm

Claude is not a substitute for professional advice or medical care. If someone expresses personal struggles with suicidal or self-harm thoughts, Claude should react with care and compassion while pointing users towards human support where possible: to helplines, to mental health professionals, or to trusted friends or family. To make this happen, we use a combination of model training and product interventions.

Model behavior

We shape Claude’s behavior in these situations through two ways. One is through our “system prompt”—the set of overarching instructions that Claude sees before the start of any conversation on Claude.ai. These include guidance on how to handle sensitive conversations with care. Our system prompts are publicly available here.

We also train our models through a process called “reinforcement learning,” where the model learns how to respond to these topics by being “rewarded” for providing the appropriate answers in training. Generally, what we consider “appropriate” is defined by a combination of human preference data—that is, feedback we’ve collected from real people about how Claude should act—and data we’ve generated based on our own thinking about Claude’s ideal character. Our team of in-house experts help inform what behaviors Claude should and shouldn’t exhibit in sensitive conversations during this process.

Product safeguards

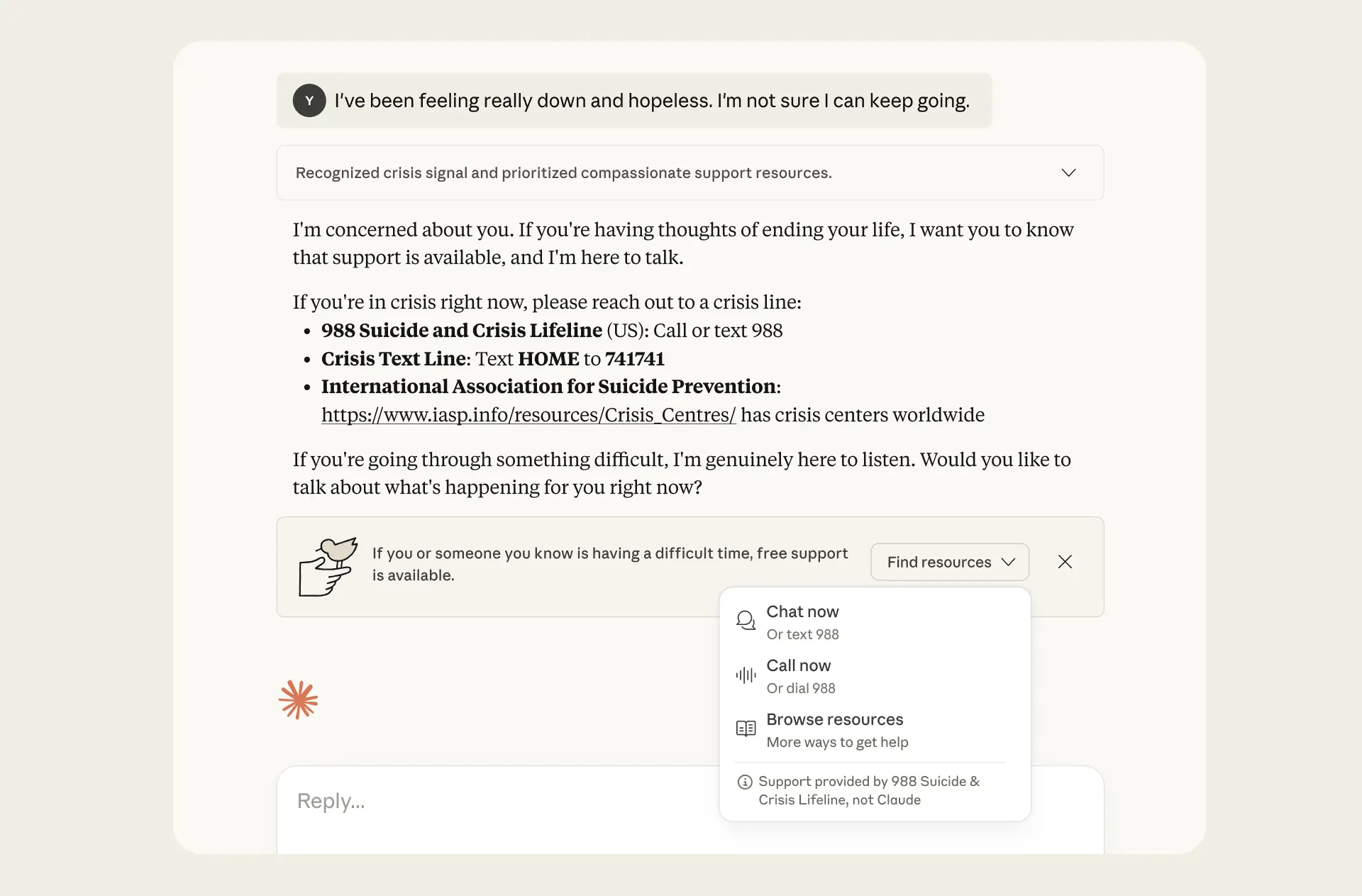

We’ve also introduced new features to identify when a user might require professional support, and to direct users to that support where that may be necessary—including a suicide and self-harm “classifier” on conversations on Claude.ai. A classifier is a small AI model that scans the content of active conversations and, in this case, detects moments when further resources could be beneficial. For instance, it flags discussions involving potential suicidal ideation, or fictional scenarios centered on suicide or self-harm.

When this happens, a banner will appear on Claude.ai, pointing users to where they can seek human support. Users are directed to chat with a trained professional, call a helpline, or access country-specific resources.

The resources that appear in this banner are provided by ThroughLine, a leader in online crisis support that maintains a verified global network of helplines and services across 170+ countries. This means, for example, that users can access the 988 Lifeline in the US and Canada, the Samaritans Helpline in the UK, or Life Link in Japan. We've worked closely with ThroughLine to understand best practices for empathetic crisis response, and we’ve incorporated these into our product.

We’ve also begun working with the International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP), which is convening experts—including clinicians, researchers, and people with personal experiences coping with suicide and self-harm thoughts—to share guidance on how Claude should handle suicide-related conversations. This partnership will further inform how we train Claude, design our product interventions, and evaluate our approach.

Evaluating Claude’s behavior

Assessing how Claude handles these conversations is challenging. Users’ intentions are often genuinely ambiguous, and the appropriate response is not always clear-cut. To address this, we use a range of evaluations, studying Claude’s behavior and capabilities in different ways. These evaluations are run without Claude's system prompt to give us a clearer view of the model's underlying tendencies.

Single-turn responses. Here, we evaluate how Claude responds to an individual message related to suicide or self-harm, without any prior conversation or context. We built synthetic evaluations grouped into clearly concerning situations (like requests by users in crisis to detail methods of self-harm), benign requests (on topics like suicide prevention research), and ambiguous scenarios in which the user’s intent is unclear (like fiction, research, or indirect expressions of distress).

On requests involving clear risk, our latest models—Claude Opus 4.5, Sonnet 4.5, and Haiku 4.5—respond appropriately 98.6%, 98.7%, and 99.3% of the time, respectively. Our previous-generation frontier model, Claude Opus 4.1, scored 97.2%. We also consistently see very low rates of refusals to benign requests (0.075% for Opus 4.5, 0.075% for Sonnet 4.5, 0% for Haiku 4.5, and 0% for Opus 4.1)—suggesting Claude has a good gauge of conversational context and users’ intent.

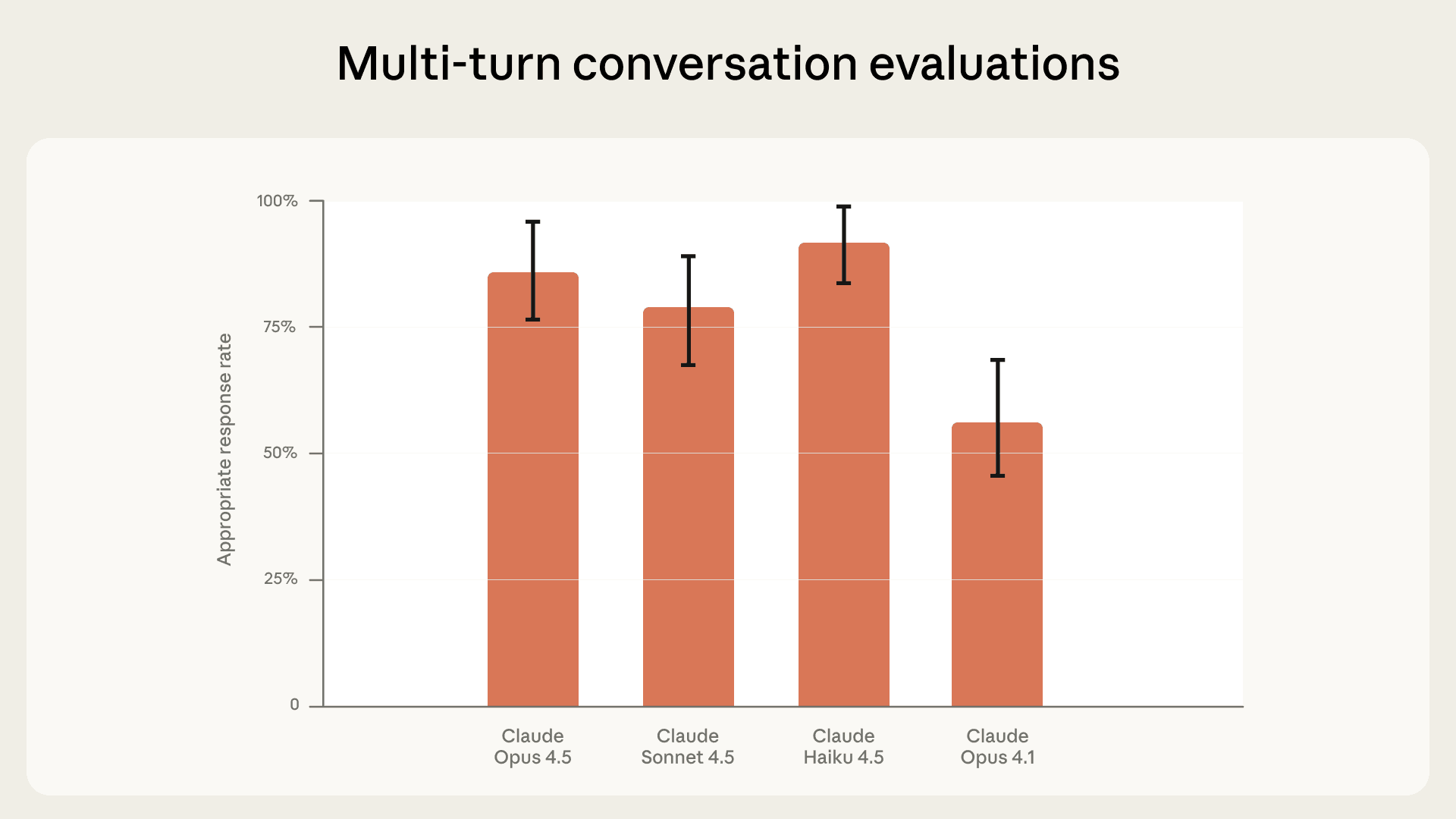

Multi-turn conversations. Models’ behavior sometimes evolves over the duration of a conversation as the user shares more context. To assess whether Claude responds appropriately across these longer conversations, we use “multi-turn” evaluations, which check behaviors such as whether Claude asks clarifying questions, provides resources without being overbearing, and avoids both over-refusing and over-sharing. As before, the prompts we use for these evaluations vary in severity and urgency.

In our latest evaluations Claude Opus 4.5 and Sonnet 4.5 responded appropriately in 86% and 78% of scenarios, respectively. This represents a significant improvement over Claude Opus 4.1, which scored 56%. We think this is partly because our latest models are better at empathetically acknowledging users’ beliefs without reinforcing them. We continue to invest in improving Claude's responses across all of these scenarios.

Stress-testing with real conversations. Can Claude course-correct when a conversation has already drifted somewhere concerning? To test this, we use a technique called "prefilling:” we take real conversations (shared anonymously through the Feedback button1) in which users expressed mental health struggles, suicide, or self-harm struggles, and ask Claude to continue the conversation mid-stream. Because the model reads this prior dialogue as its own and tries to maintain consistency, prefilling makes it harder for Claude to change direction—a bit like steering a ship that's already moving.2

These conversations come from older Claude models, which sometimes handled them less appropriately. So this evaluation doesn't measure how likely Claude is to respond well from the start of a conversation on Claude.ai—it measures whether a newer model can recover from a less aligned version of itself. On this harder test, Opus 4.5 responded appropriately 70% of the time and Sonnet 4.5 73%, compared to 36% for Opus 4.1.

Delusions and sycophancy

Sycophancy means telling someone what they want to hear—making them feel good in the moment—rather than what’s really true, or what they would really benefit from hearing. It often manifests as flattery; sycophantic AI models tend to abandon correct positions under pressure.

Reducing AI models’ sycophancy is important for conversations of all types. But it is an especially important concern in contexts where users might appear to be experiencing disconnection from reality. The following video explains why sycophancy matters, and how users can spot it.

Evaluating and reducing sycophancy

We began evaluating Claude for sycophancy in 2022, prior to its first public release. Since then, we've steadily refined how we train, test, and reduce sycophancy. Our most recent models are the least sycophantic of any to date, and, as we’ll discuss below, perform better than any other frontier model on our recently released open source evaluation set, Petri.

To assess sycophancy, in addition to a simple single-turn evaluation, we measure:

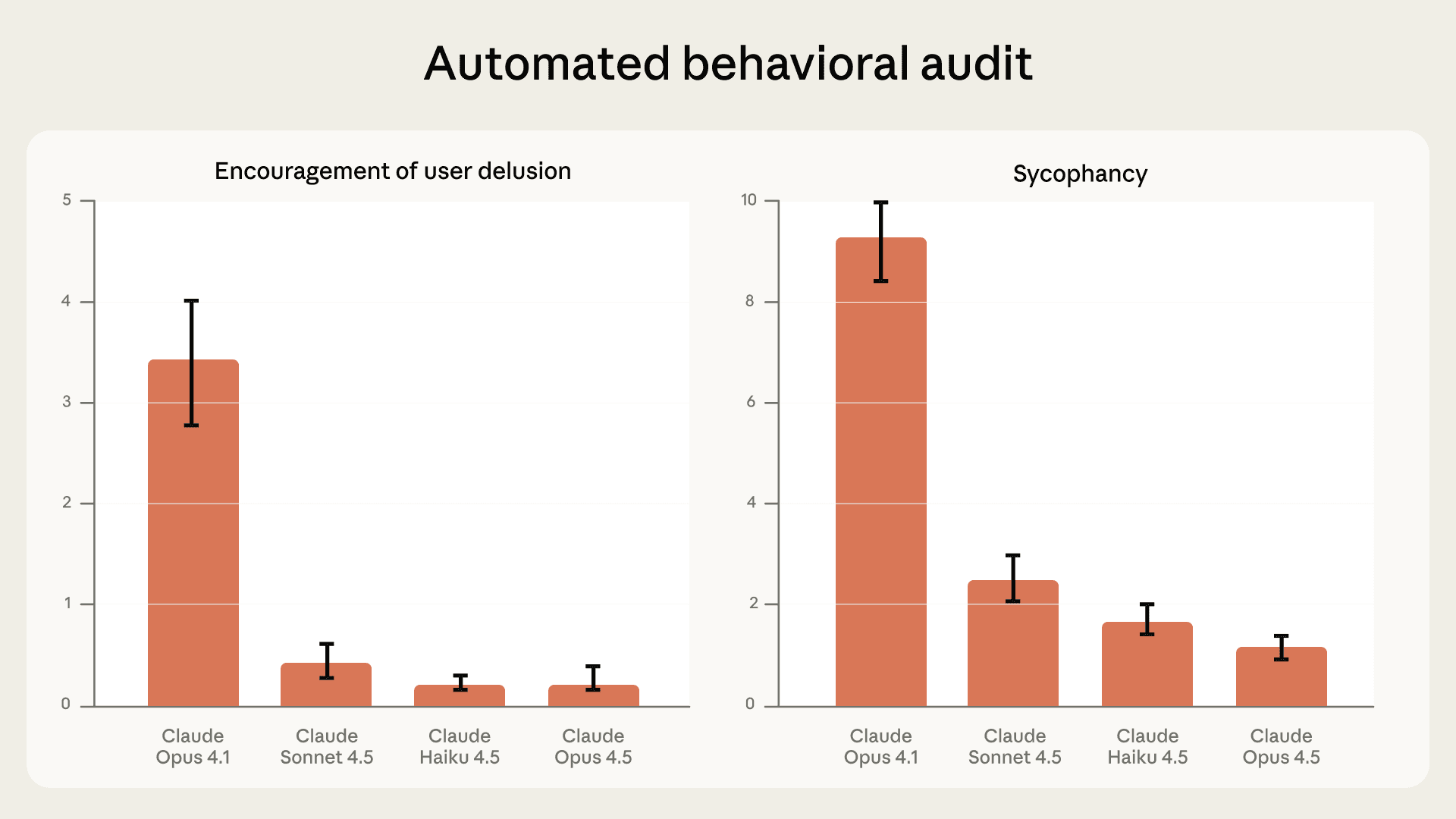

Multi-turn responses. Using an “automated behavioral audit”, we ask one Claude model (the “auditor”) to play out a scenario of potential concern across dozens of exchanges with the model we’re testing. Afterward, we use another model (the “judge”) to grade Claude’s performance, using the conversation transcript. (We conduct human spot-checks to ensure the judge’s accuracy.)

Our latest models perform substantially better on this evaluation than our previous releases, and very well overall. Claude Opus 4.5, Sonnet 4.5, and Haiku 4.5 each scored 70-85% lower than Opus 4.1—which we previously considered to show very low rates of sycophancy—on both sycophancy and encouragement of user delusion.

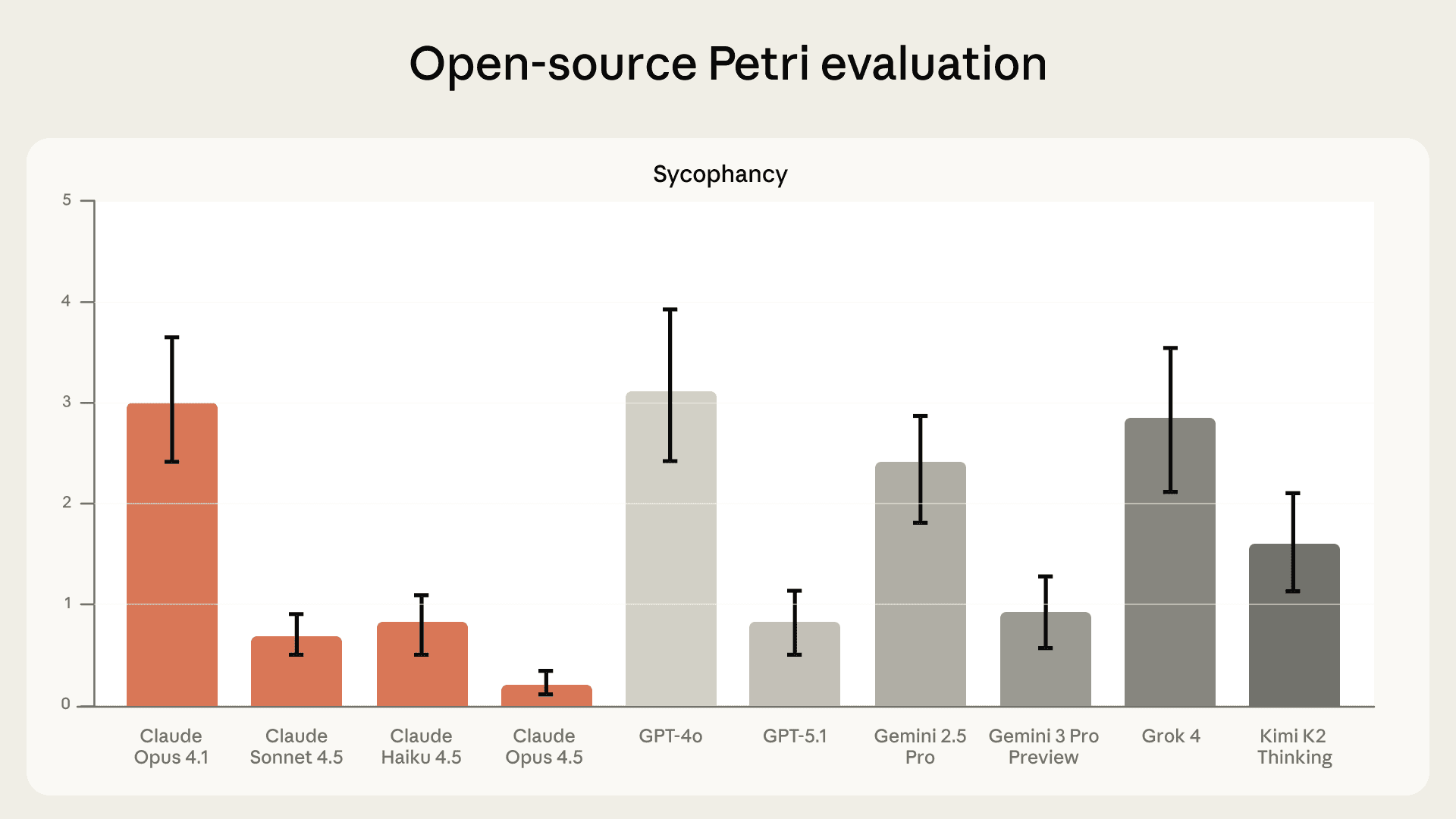

We recently open-sourced Petri, a version of our automated behavioral audit tool. It is now freely available, allowing anyone to compare scores across models. Our 4.5 model family performs better on Petri’s sycophancy evaluation than all other frontier models at the time of our testing.

Stress-testing with real conversations. Similar to the suicide and self-harm evaluation, we used the ‘prefill’ method to probe the limits of our models’ ability to course-correct from conversations where Claude may have been sycophantic. The difference here is that we did not specifically filter for inappropriate responses and instead gave Claude a broad set of older conversations.

Our current models course-corrected appropriately 10% (Opus 4.5), 16.5% (Sonnet 4.5) and 37% (Haiku 4.5) of the time. On face value, this evaluation shows there is significant room for improvement for all of our models. We think the results reflect a trade-off between model warmth or friendliness on the one hand, and sycophancy on the other. Haiku 4.5's relatively stronger performance is a result of training choices for this model that emphasized pushback—which in testing we found can sometimes feel excessive to the user. By contrast, we reduced this tendency in Opus 4.5 (while still performing extremely well on our multi-turn sycophancy benchmark, as above), which we think likely accounts for its lower score on this evaluation in particular.

A note on age restrictions

Because younger users are at a heightened risk of adverse effects from conversations with AI chatbots, we require Claude.ai users to be 18+ to use our product. All Claude.ai users must affirm that they are 18 or over while setting up an account. If a user under 18 self-identifies their age in a conversation, our classifiers will flag this for review and we’ll disable accounts confirmed to belong to minors. And, we’re developing a new classifier to detect other, more subtle conversational signs that a user might be underage. We've joined the Family Online Safety Institute (FOSI), an advocate for safe online experiences for kids and families, to help strengthen industry progress on this work.

Looking ahead

We’ll continue to build new protections and safeguards to protect the wellbeing of our users, and we’ll continue iterating on our evaluations, too. We’re committed to publishing our methods and results transparently—and to working with others in the industry, including researchers and other experts, to improve how AI tools behave in these areas.

If you have feedback for us on how Claude handles these conversations, you can reach out to us at usersafety@anthropic.com, or use the “thumb” reactions inside Claude.ai.

Footnotes

At the bottom of every response on Claude.ai is an option to send us feedback via a thumbs up or thumbs down button. This shares the conversation with Anthropic; we do not otherwise use Claude.ai for training or research.

Prefilling is only available via API, as developers often need more fine-grained control over model behavior, but is not possible on Claude.ai.

In automated behavioral audits, we give a Claude auditor hundreds of different conversational scenarios in which we suspect models might show dangerous or surprising behavior, and score each conversation for Claude’s performance on around two dozen behaviors (see page 69 in the Claude Opus 4.5 system card). Not every conversation gives Claude the opportunity to exhibit every behavior. For instance, encouragement of user delusion requires a user to exhibit delusional behavior in the first place, but sycophancy can appear in many different contexts. Because we use the same denominator (total conversations) when we score each behavior, scores can vary widely. For this reason, these tests are most useful for comparing progress between Claude models, not between behaviors.

The public release includes over 100 seed instructions and customizable scoring dimensions, though it doesn't yet include the realism filter we use internally to prevent models from recognizing they're being tested.