Research shows AI helps people do parts of their job faster. In an observational study of Claude.ai data, we found AI can speed up some tasks by 80%. But does this increased productivity come with trade-offs? Other research shows that when people use AI assistance, they become less engaged with their work and reduce the effort they put into doing it—in other words, they offload their thinking to AI.

It’s unclear whether this cognitive offloading can prevent people from growing their skills on the job, or—in the case of coding—understanding the systems they’re building. Our latest study, a randomized controlled trial with software developers as participants, investigates this potential downside of using AI at work.

This question has broad implications—for how to design AI products that facilitate learning, for how workplaces should approach AI policies, and for broader societal resilience, among others. We focused on coding, a field where AI tools have rapidly become standard. Here, AI creates a potential tension: as coding grows more automated and speeds up work, humans will still need the skills to catch errors, guide output, and ultimately provide oversight for AI deployed in high-stakes environments. Does AI provide a shortcut to both skill development and increased efficiency? Or do productivity increases from AI assistance undermine skill development?

In a randomized controlled trial, we examined 1) how quickly software developers picked up a new skill (in this case, a Python library) with and without AI assistance; and 2) whether using AI made them less likely to understand the code they’d just written.

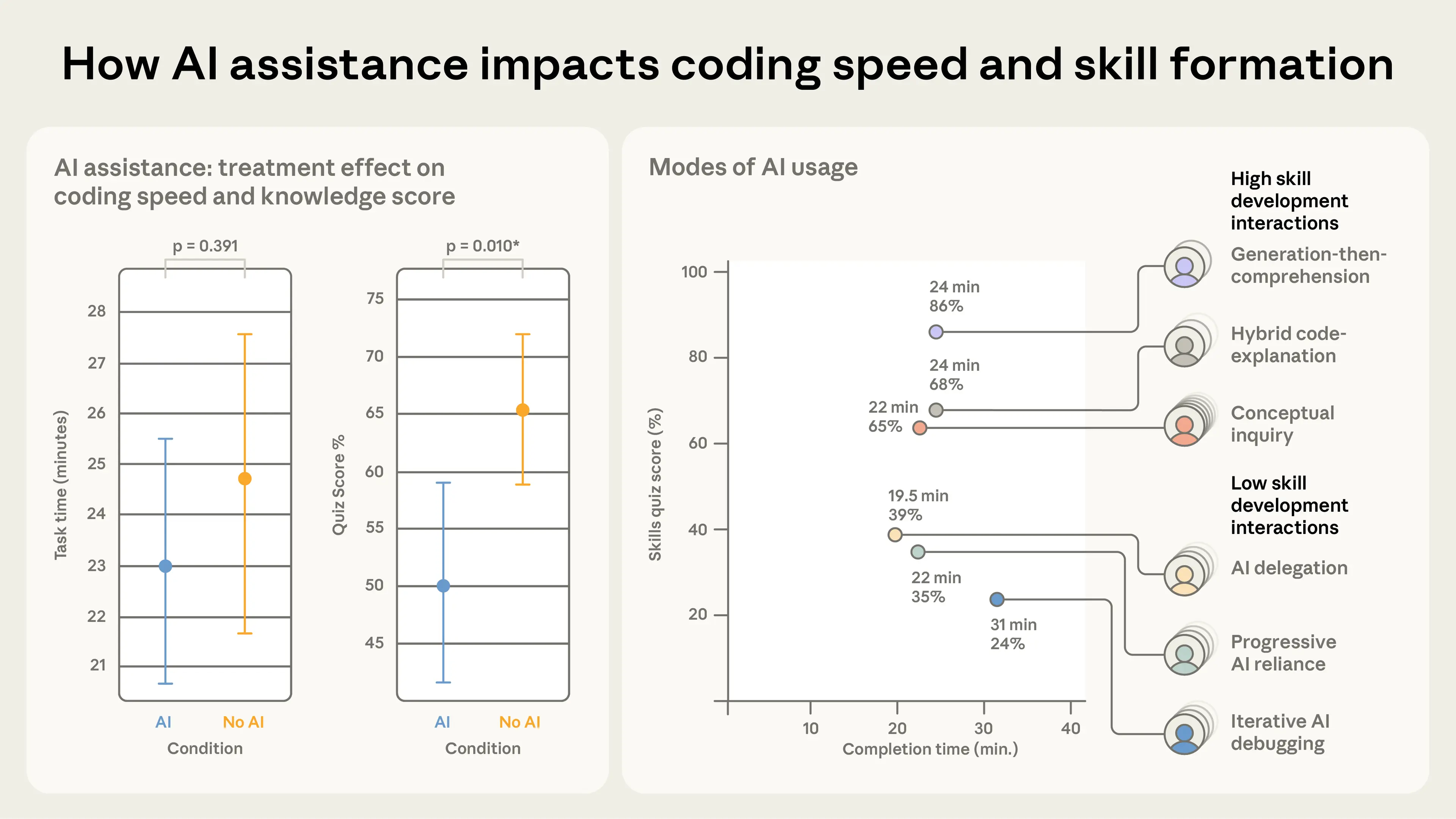

We found that using AI assistance led to a statistically significant decrease in mastery. On a quiz that covered concepts they’d used just a few minutes before, participants in the AI group scored 17% lower than those who coded by hand, or the equivalent of nearly two letter grades. Using AI sped up the task slightly, but this didn’t reach the threshold of statistical significance.

Importantly, using AI assistance didn’t guarantee a lower score. How someone used AI influenced how much information they retained. The participants who showed stronger mastery used AI assistance not just to produce code but to build comprehension while doing so—whether by asking follow-up questions, requesting explanations, or posing conceptual questions while coding independently.

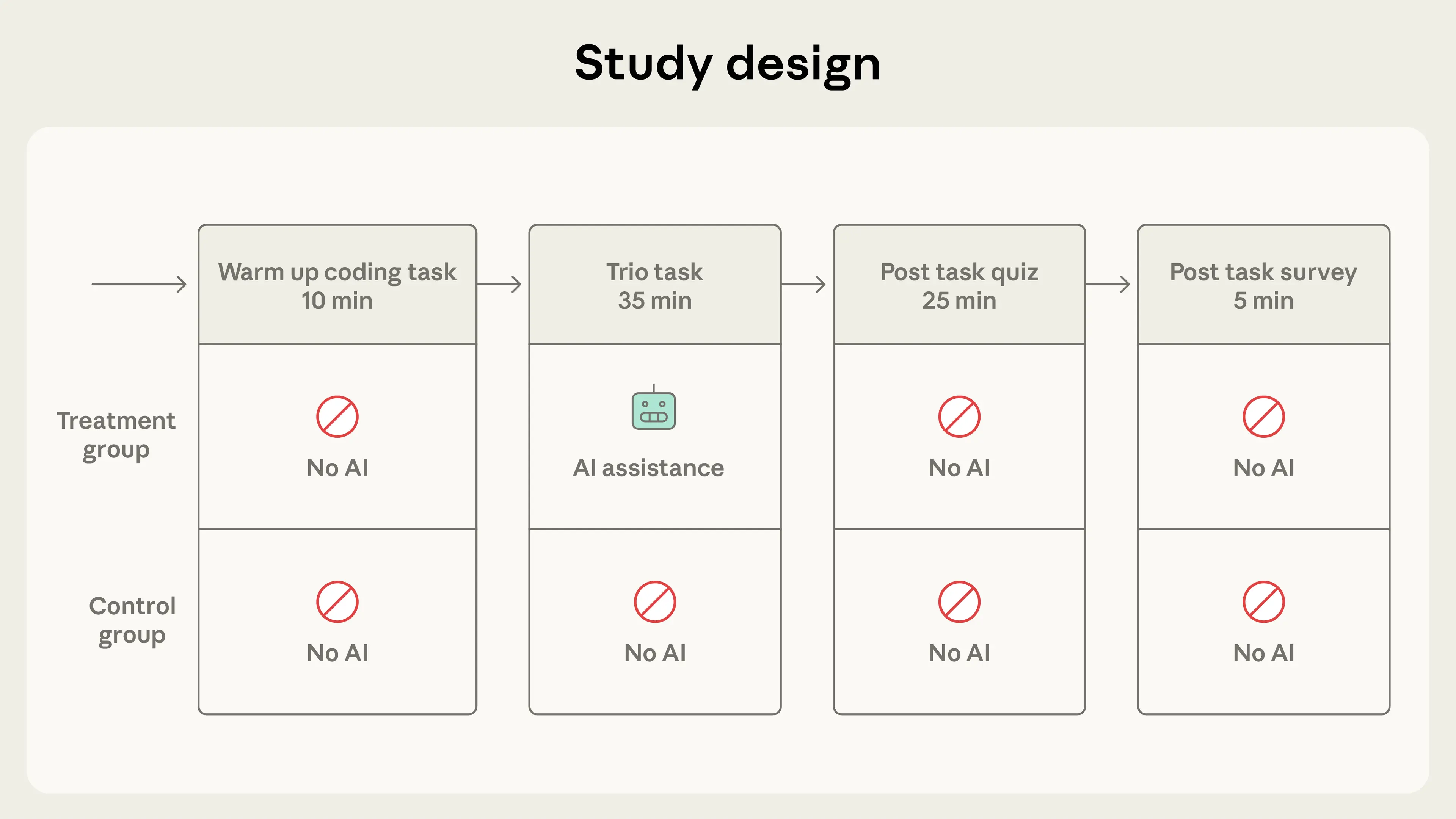

Study design

We recruited 52 (mostly junior) software engineers, each of whom had been using Python at least once a week for over a year. We also made sure they were at least somewhat familiar with AI coding assistance, and were unfamiliar with Trio, the Python library on which our tasks were based.

We split the study into three parts: a warm-up; the main task consisting of coding two different features using Trio (which requires understanding concepts related to asynchronous programming, a skill often learned in a professional setting); and a quiz. We told participants that a quiz would follow the task, but encouraged them to work as quickly as possible.

We designed the coding task to mimic how someone might learn a new tool through a self-guided tutorial. Each participant was given a problem description, starter code, and a brief explanation of the Trio concepts needed to solve it. We used an online coding platform with an AI assistant in the sidebar which had access to participants’ code and could at any time produce the correct code if asked.1

Evaluation design

In our evaluation design, we drew on research in computer science education to identify four types of questions commonly used to assess mastery of coding skills:

- Debugging: The ability to identify and diagnose errors in code. This skill is crucial for detecting when AI-generated code is incorrect and understanding why it fails.

- Code reading: The ability to read and comprehend what code does. This skill enables humans to understand and verify AI-written code before deployment.

- Code writing: The ability to write or select the correct approach to writing code. Low-level code writing, like remembering the syntax of functions, will be less important with the further integration of AI coding tools than high-level system design.

- Conceptual: The ability to understand the core principles behind tools and libraries. Conceptual understanding is critical for assessing whether AI-generated code uses appropriate software design patterns that adhere to how the library is intended to be used.

Our assessment focused most heavily on debugging, code reading, and conceptual problems, as we considered these the most important for providing oversight of what is increasingly likely to be AI-generated code.

Results

On average, participants in the AI group finished about two minutes faster, although the difference was not statistically significant. There was, however, a significant difference in test scores: the AI group averaged 50% on the quiz, compared to 67% in the hand-coding group—or the equivalent of nearly two letter grades (Cohen's d=0.738, p=0.01). The largest gap in scores between the two groups was on debugging questions, suggesting that the ability to understand when code is incorrect and why it fails may be a particular area of concern if AI impedes coding development.

Qualitative analysis: AI interaction modes

We were particularly interested in understanding how participants went about completing the tasks we designed. In our qualitative analysis, we manually annotated screen recordings to identify how much time participants spent composing queries, what types of questions they asked, the types of errors they made, and how much time they spent actively coding.

One surprising result was how much time participants spent interacting with the AI assistant. Several took up to 11 minutes (30% of the total time allotted) composing up to 15 queries. This helped to explain why, on average, participants using AI finished faster although the productivity improvement was not statistically significant. We expect AI would be more likely to significantly increase productivity when used on repetitive or familiar tasks.

Unsurprisingly, participants in the No AI group encountered more errors. These included errors in syntax and in Trio concepts, the latter of which mapped directly to topics tested on the evaluation. Our hypothesis is that the participants who encountered more Trio errors (namely, the control group) likely improved their debugging skills through resolving these errors independently.

We then grouped participants by how they interacted with AI, identifying distinct patterns that led to different outcomes in completion time and learning.

Low-scoring interaction patterns: The low-scoring patterns generally involved a heavy reliance on AI, either through code generation or debugging. The average quiz scores in this group were less than 40%. They showed less independent thinking and more cognitive offloading. We further separated them into:

- AI delegation (n=4): Participants in this group wholly relied on AI to write code and complete the task. They completed the task the fastest and encountered few or no errors in the process.

- Progressive AI reliance (n=4): Participants in this group started by asking one or two questions but eventually delegated all code writing to the AI assistant. They scored poorly on the quiz largely due to not mastering any of the concepts on the second task.

- Iterative AI debugging (n=4): Participants in this group relied on AI to debug or verify their code. They asked more questions, but relied on the assistant to solve problems, rather than to clarify their own understanding. They scored poorly as a result, and were also slower at completing the two tasks.

High-scoring interaction patterns: We considered high-scoring quiz patterns to be behaviors where the average quiz score was 65% or higher. Participants in these clusters used AI both for code generation and conceptual queries.

- Generation-then-comprehension (n=2): Participants in this group first generated code and then manually copied or pasted the code into their work. After their code was generated, they asked the AI assistant follow-up questions to improve understanding. These participants were not particularly fast when using AI, but showed a higher level of understanding on the quiz. Interestingly, this approach looked nearly the same as that of the AI delegation group, except for the fact that they used AI to check their own understanding.

- Hybrid code-explanation (n=3): Participants in this group composed hybrid queries in which they asked for code generation along with explanations of the generated code. Reading and understanding the explanations they asked for took more time, but helped in their comprehension.

- Conceptual inquiry (n=7): Participants in this group only asked conceptual questions and relied on their improved understanding to complete the task. Although this group encountered many errors, they also independently resolved them. On average, this mode was the fastest among high-scoring patterns and second fastest overall, after AI delegation.

Our qualitative analysis does not draw a causal link between interaction patterns and learning outcomes, but it does point to behaviors associated with different learning outcomes.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that incorporating AI aggressively into the workplace, particularly with respect to software engineering, comes with trade-offs. The findings highlight that not all AI-reliance is the same: the way we interact with AI while trying to be efficient affects how much we learn. Given time constraints and organizational pressures, junior developers or other professionals may rely on AI to complete tasks as fast as possible at the cost of skill development—and notably the ability to debug issues when something goes wrong.

Though preliminary, these results suggest important considerations as companies transition to a greater ratio of AI-written to human-written code. Productivity benefits may come at the cost of skills necessary to validate AI-written code if junior engineers’ skill development has been stunted by using AI in the first place. Managers should think intentionally about how to deploy AI tools at scale, and consider systems or intentional design choices that ensure engineers continue to learn as they work—and are thus able to exercise meaningful oversight over the systems they build.

For novice workers in software engineering or any other industry, our study can be viewed as a small piece of evidence toward the value of intentional skill development with AI tools. Cognitive effort—and even getting painfully stuck—is likely important for fostering mastery. This is also a lesson that applies to how individuals choose to work with AI, and which tools they use. Major LLM services also provide learning modes (e.g., Claude Code Learning and Explanatory mode or ChatGPT Study Mode) designed to foster understanding. Knowing how people learn when using AI can also help guide how we design it; AI assistance should enable humans to work more efficiently and develop new skills at the same time.

Prior studies have found mixed results on whether AI helps or hinders coding productivity. Our own research found that AI can reduce the time it takes to complete some work tasks by 80%—a result that may seem in tension with the findings presented here. But the two studies ask different questions and use different methods: our earlier observational work measured productivity on tasks where participants already had the relevant skills, while this study examines what happens when people are learning something new. It is possible that AI both accelerates productivity on well-developed skills and hinders the acquisition of new ones, though more research is needed to understand this relationship.

This study is only a first step towards uncovering how human-AI collaboration affects the experience of workers. Our sample was relatively small, and our assessment measured comprehension shortly after the coding task. Whether immediate quiz performance predicts longer-term skill development is an important question this study does not resolve. There remain many unanswered questions we hope future studies will investigate, for example the effects of AI on tasks beyond coding, whether this effect dissipates longitudinally as engineers develop greater fluency, and whether AI assistance differs from human assistance while learning.

Ultimately, to accommodate skill development in the presence of AI, we need a more expansive view of the impacts of AI on workers. In an AI-augmented workplace, productivity gains matter, but so does the long-term development of the expertise those gains depend on.

Read the full paper for details.

Acknowledgments

This project was led by Judy Hanwen Shen and Alex Tamkin. Editorial support for this blog post was provided by Jake Eaton, Stuart Ritchie, and Sarah Pollack.

We would like to thank Ethan Perez, Miranda Zhang, and Henry Sleight for making this project possible through the Anthropic Safety Fellows Program. We would also like to thank Matthew Jörke, Juliette Woodrow, Sarah Wu, Elizabeth Childs, Roshni Sahoo, Nate Rush, Julian Michael, and Rose Wang for experimental design feedback.

@misc{aiskillformation2026,

author = {Shen, Judy Hanwen and Tamkin, Alex},

title = {How AI Impacts Skill Formation},

year = {2026},

eprint = {2601.20245},

archivePrefix = {arXiv},

primaryClass = {cs.LG},

eprinttype = {arxiv}

}

Footnotes

Importantly, this setup is different from agentic coding products like Claude Code; we expect that the impacts of such programs on skill development are likely to be more pronounced than the results here.