Introducing Anthropic Interviewer: What 1,250 professionals told us about working with AI

We’re launching a new tool, Anthropic Interviewer, to help understand people’s perspectives on AI. In this research post, we introduce the tool, describe a test of it on a sample of professionals, and discuss our early findings. We also discuss future work in this direction that we can now explore with the development of this tool and through partnerships with creatives, scientists, and teachers.

Introduction

Millions of people now use AI every day. As a company developing AI systems, we want to know how and why they’re doing so, and how it affects them. In part, this is because we want to use people’s feedback to develop better products—but it’s also because understanding people’s interactions with AI is one of the great sociological questions of our time.

We recently designed a tool to investigate patterns of AI use while protecting our users’ privacy. It enabled us to analyze changing patterns of AI use across the economy. But the tool only allowed us to understand what was happening within conversations with Claude. What about what comes afterwards? How are people actually using Claude’s outputs? How do they feel about it? What do they imagine the role of AI to be in their future? If we want a comprehensive picture of AI’s changing role in people’s lives, and to center humans in the development of models, we need to ask people directly.

Such a project would require us to run many hundreds of interviews. Here, we enlisted AI to help us do so. We built an interview tool called Anthropic Interviewer. Powered by Claude, Anthropic Interviewer runs detailed interviews automatically at unprecedented scale, feeding its results back to human researchers for analysis. This is a new step in understanding the wants and needs of our users, as well as gathering data for the analysis of AI’s societal and economic impacts.

To test Anthropic Interviewer, we had it run 1,250 interviews with professionals—the general workforce (N=1,000), scientists (N=125), and creatives (N=125)—about their views on AI. We’re publicly releasing all interview data from this initial test (with participant consent) for researchers to explore; we provide our own analysis below. Briefly, here are some examples of what we found:

- In our sample, people are optimistic about the role AI plays in their work. Positive sentiments characterized the majority of topics discussed. However, a small number of topics such as educational integration, artist displacement, and security concerns, came with more pessimistic outlooks.

- People from the general workforce want to preserve tasks that define their professional identity while delegating routine work to AI. They envision futures where routine tasks are automated and their role shifts to overseeing AI systems.

- Creatives are using AI to increase their productivity despite peer judgement and anxiety about the future. They are navigating both the immediate stigma of AI use in creative communities and deeper concerns about economic displacement and the erosion of human creative identity.

- Scientists want AI partnership but can't yet trust it for core research. Scientists uniformly expressed a desire for AI that could generate hypotheses and design experiments. But at present, they confined their actual use to other tasks like writing manuscripts or debugging analysis code.

General workforce

| Pessmistic | Optimistic |

|---|---|

| Career adaptation. Trucking dispatcher: “I'm always trying to figure out things that humans offer to the industry that can't be automated and really hone in on that aspect like the personalized human interactions. However, that is not something that I think will be necessary in the long run. I'm still trying to figure out what skills would be good to work on that AI can't ‘take over.’” | Societal perspectives. Office assistant: “It's a tool to me like a computer was, or a type writer was in the day—computers didn't get rid of mathematicians, they just made them able to do more and that is where I see AI going in the best possible future.” |

| Writing independence. Salesperson: “I hear from colleagues that they can tell when email correspondence is AI generated and they have a slightly negative regard for the sender. They feel slighted that the sender is ‘too lazy’ to send them a personal note and push it onto AI to do it.” | Educational integration. Special education teacher: “I am hoping that AI will be a more collaborative partner that will help me better manage my time and help me expand creatively so I can offer my students a wide variety of activities and assignments that I may not have been able to come up with on my own.” |

Creatives

| Pessimistic | Optimistic |

|---|---|

| Control boundaries. Gamebook writer: “During these storytelling sessions, I would say that there's only the illusion of collaboration for the most part… there’s rarely a point where I’ve really felt like the AI is driving the creative decision-making.” | Workflow automation. Social media manager: “I’m less stressed, honestly. It has created a ton of efficiency for me so I can focus on my favorite aspects of the job (filming and editing)”. |

| Writer displacement. Creative fiction writer: “A novel written by AI might have a great plot and be technically brilliant. But it won’t have the deeper nuances that only a human can weave throughout the story.” | Music production. Music producer: “Sometimes, when it comes time to add lyrics, I’ll ask ChatGPT or Claude for lists of interesting word pairings. Just getting a long list to try out over the instrumental often leads to finding a hook or at least a seed for a song idea.” |

Scientists

| Pessimistic | Optimistic |

|---|---|

| Security concerns. Medical scientist: “Our confidence in AI just isn’t high enough at the moment to trust it with our data. We’re also a commercial entity so there’s a bit of concern over confidentially with data that we might share with an AI system.” | Research assistance. Molecular biologist: “If AI could integrate and normalize all this data in a single repository, it could be a very exciting thing for biological discovery. You could see how expression dynamics change across cell models, tissue types, disease states, and more.” |

| Content verification. Economist: “What I would really like from an AI would be the ability to accurately grab information, summarise it and use it to write the core of a funding application. AI generally writes well; the problem now is that I just can’t rely on it not hallucinating, or to put it bluntly, lying.” | Code development. Food scientist: “Honestly I wouldn’t have known how to help my student with her code if something was off without AI tools.” |

Method

This initial test explored how workers integrate AI into their professional practice and how they feel about its role in their future. We ran interviews to produce qualitative data, and supplemented them with quantitative data from surveys where participants answered questions on their behavioral and occupational backgrounds. We also had a separate AI analysis tool read the interview transcripts and cluster together emergent, overarching themes from the unstructured data—for example, on the percentage of participants who mentioned a specific topic or expressed a specific view in their interview.

Participants

We used Anthropic Interviewer to conduct interviews with 1,250 professionals. We intend for the tool to interview general Claude.ai users, but for this initial test, we sought participants working across a range of professions and engaged them through crowdworker platforms (all participants had an occupation other than crowdworking that was their main job).

1,000 of our participants were recruited from a general sample of occupations (that is, we did not select participants from specific jobs). Of that group, the largest subgroups came from educational instruction (17%), computer and mathematical occupations (16%), and arts, design, entertainment, and media (14%).

We also recruited two specialist samples of 125 participants each. The first was from creative professions: predominantly writers and authors (48% of the sample), and visual artists (21%), with smaller groups of filmmakers, designers, musicians, and craft workers. The second was from science, which included physicists (9%), chemists (9%), chemical engineers (7%), and data scientists (6%), with representation across 50+ other distinct scientific disciplines.

We chose to add these two specialist subgroups because these represent professional domains where AI’s role remains contested and is rapidly evolving. We hypothesized that creatives and scientists would reveal distinct patterns of AI adoption and professional concerns.

All participants provided informed consent for us to analyze their interview data for research purposes and for us to release the transcripts publicly.

How Anthropic Interviewer works

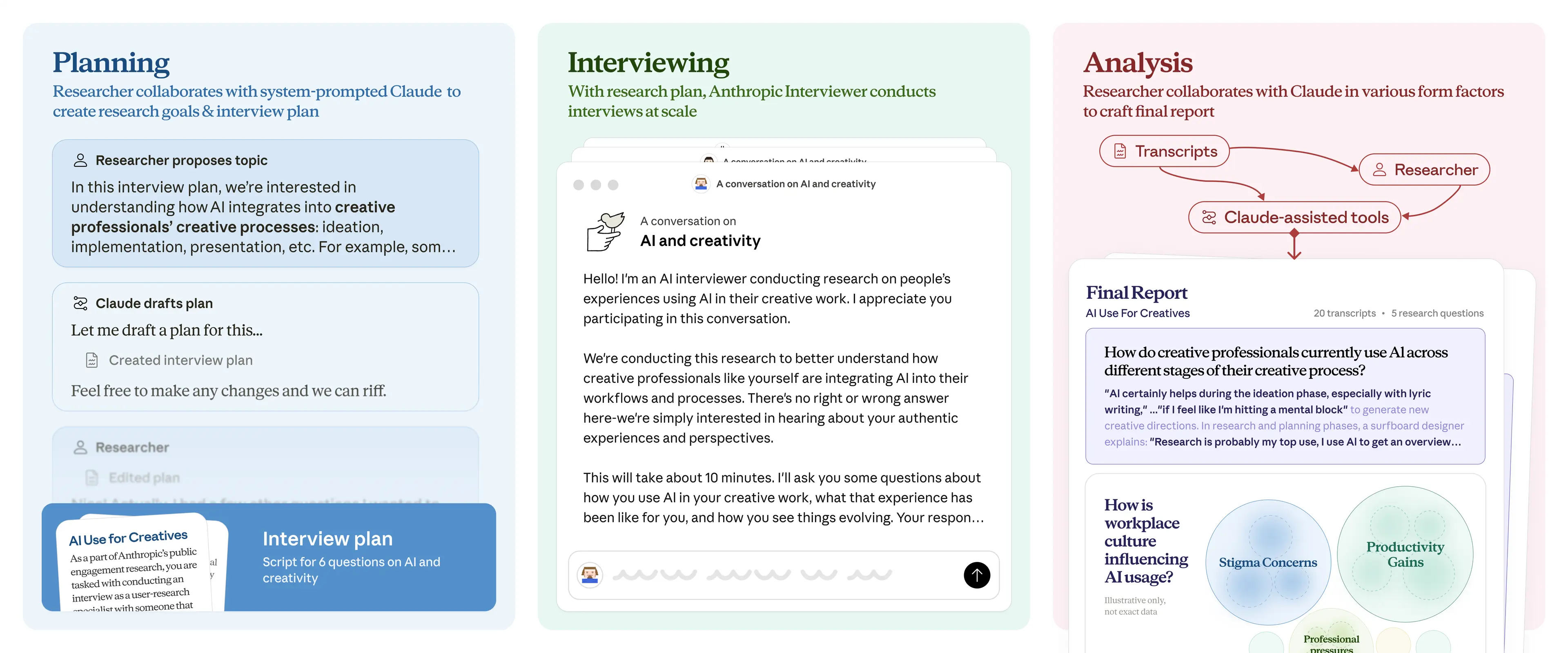

Anthropic Interviewer operates in three stages: planning, interviewing, and analysis. Below, we describe each of them in turn.

Planning

In this phase, Anthropic Interviewer creates an interview rubric that allows it to focus on the same overall research questions across hundreds or thousands of interviews, but which is still flexible enough to accommodate variations and tangents that might occur in individual interviews.

We developed a system prompt—a set of overall instructions for how the AI model is to work—to give Anthropic Interviewer its methodology. This was where we included hypotheses regarding each sample, as well as best practices for creating an interview plan (this was established in collaboration with our user research team).

After putting the system prompt in place, Anthropic Interviewer used its knowledge of our research goal (see section below) to generate specific questions and a planned conversation flow. There was then a review phase where human researchers collaborated with Anthropic Interviewer to make any necessary edits to finalize the plan.

Interviewing

Anthropic Interviewer then conducted real-time, adaptive interviews following its interview plan. At this stage, we included a system prompt to instruct Anthropic Interviewer how to use best practices for interviews.

The interviews conducted by Anthropic Interviewer appeared on Claude.ai and lasted about 10-15 minutes with each participant.

Analysis

Once interviews were complete, a human researcher collaborated with Anthropic Interviewer to analyze the transcripts. Anthropic Interviewer’s analysis step takes as input the initial interview plan and outputs answers to the research questions alongside illustrative quotations. At this stage, we also used our automated AI analysis tool to identify emergent themes and quantify their prevalence across participants.

Research goals

As described above, Anthropic Interviewer was made aware of the research goals through its system prompt, and ran its interviews in such a way as to address them. Note that, in this initial study, our main intention was to perform a practical test of Anthropic Interviewer; the goals below nonetheless provided interesting data which we analyze below.

The following were the main research goals for each subsample:

- General workforce. “Understand how individuals integrate AI tools into their professional workflows, exploring usage patterns, task preferences, and interaction styles to gain insights into the evolving relationship between humans and AI in workplace contexts.”

- Creatives. “To understand how creative professionals currently integrate AI into their creative processes, their experiences with AI’s impact on their work, and their vision for the future relationship between AI and human creativity.”

- Scientists. “To understand how AI systems integrate into scientists' daily research workflows, examining their current usage patterns, perceived value, trust levels, and barriers to adoption across different stages of the scientific process.”

Results

Below we discuss what we discovered in our interviews and provide quantitative data from our survey and thematic analysis.

AI’s impact in the general workforce

Overall, the members of our general sample of professionals described AI as a boost to their productivity. In the survey, 86% of professionals reported that AI saves them time and 65% said they were satisfied with the role AI plays in their work.

One theme that surfaced is how workplace dynamics affect the adoption of AI. 69% of professionals mentioned the social stigma that can come with using AI tools at work—one fact-checker told Anthropic Interviewer: “A colleague recently said they hate AI and I just said nothing. I don’t tell anyone my process because I know how a lot of people feel about AI.”

Whereas 41% of interviewees said they felt secure in their work and believed human skills are irreplaceable, 55% expressed anxiety about AI’s impact on their future. 25% of the group expressing anxiety said they set boundaries around AI use (e.g. an educator always creating lesson plans themselves), while 25% adapted their workplace roles, taking on additional responsibilities or pursuing more specialized tasks.

Approaches to AI use varied widely. One data quality manager deliberately chose learning over automation: “I try to think about it like studying a foreign language—just using a translator app isn’t going to teach you anything, but having a tutor who can answer questions and customize for your needs is really going to help.” A marketer took a flexible approach: “I am trying to diversify while keeping a strong niche.” An interpreter was already preparing to leave the field entirely: “I believe AI will eventually replace most interpreters... so I’m already preparing for a career switch, possibly by getting a diploma and getting into a different trade.” Notably, only 8% of professionals expressed anxiety without any clear remediation plan.

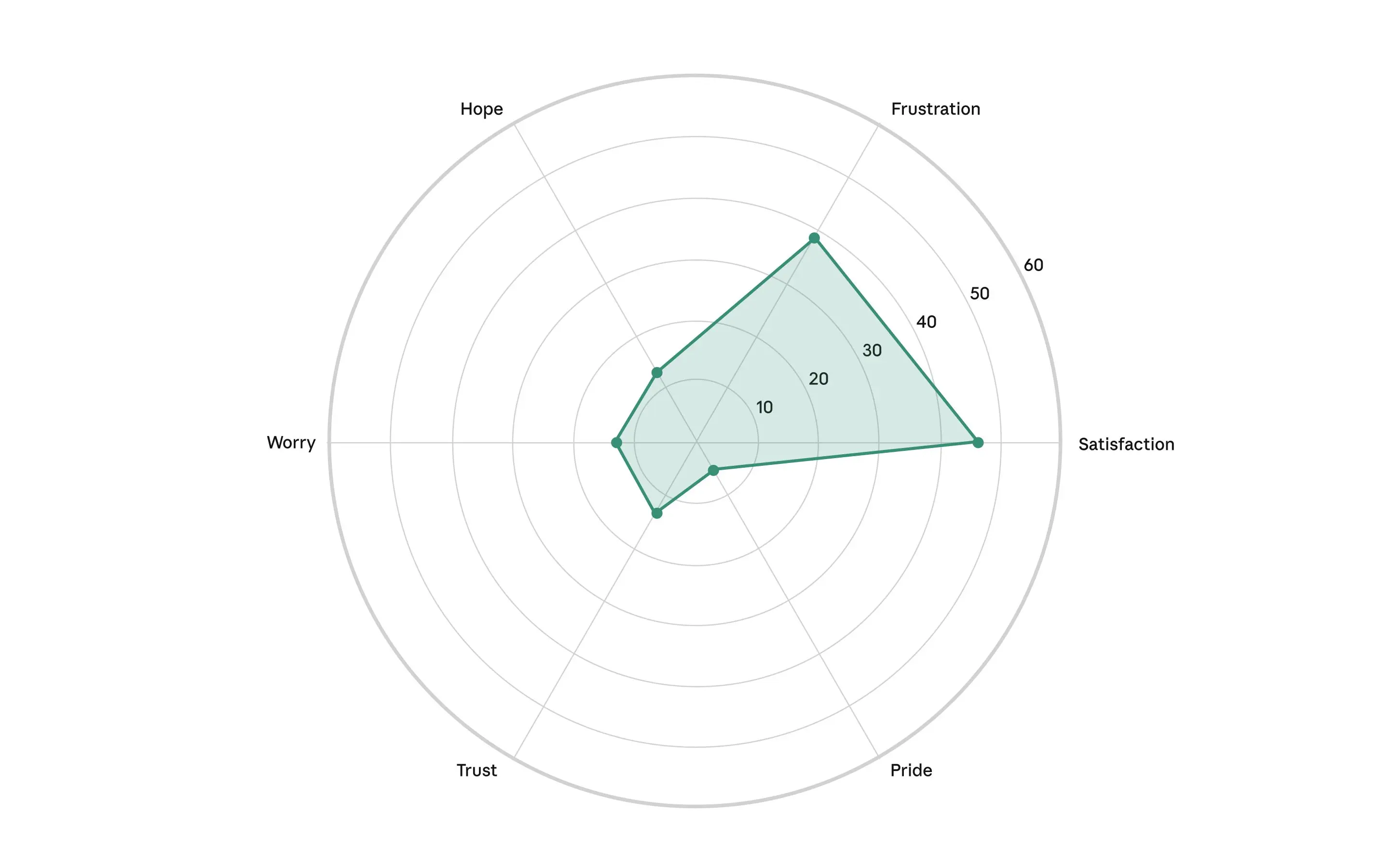

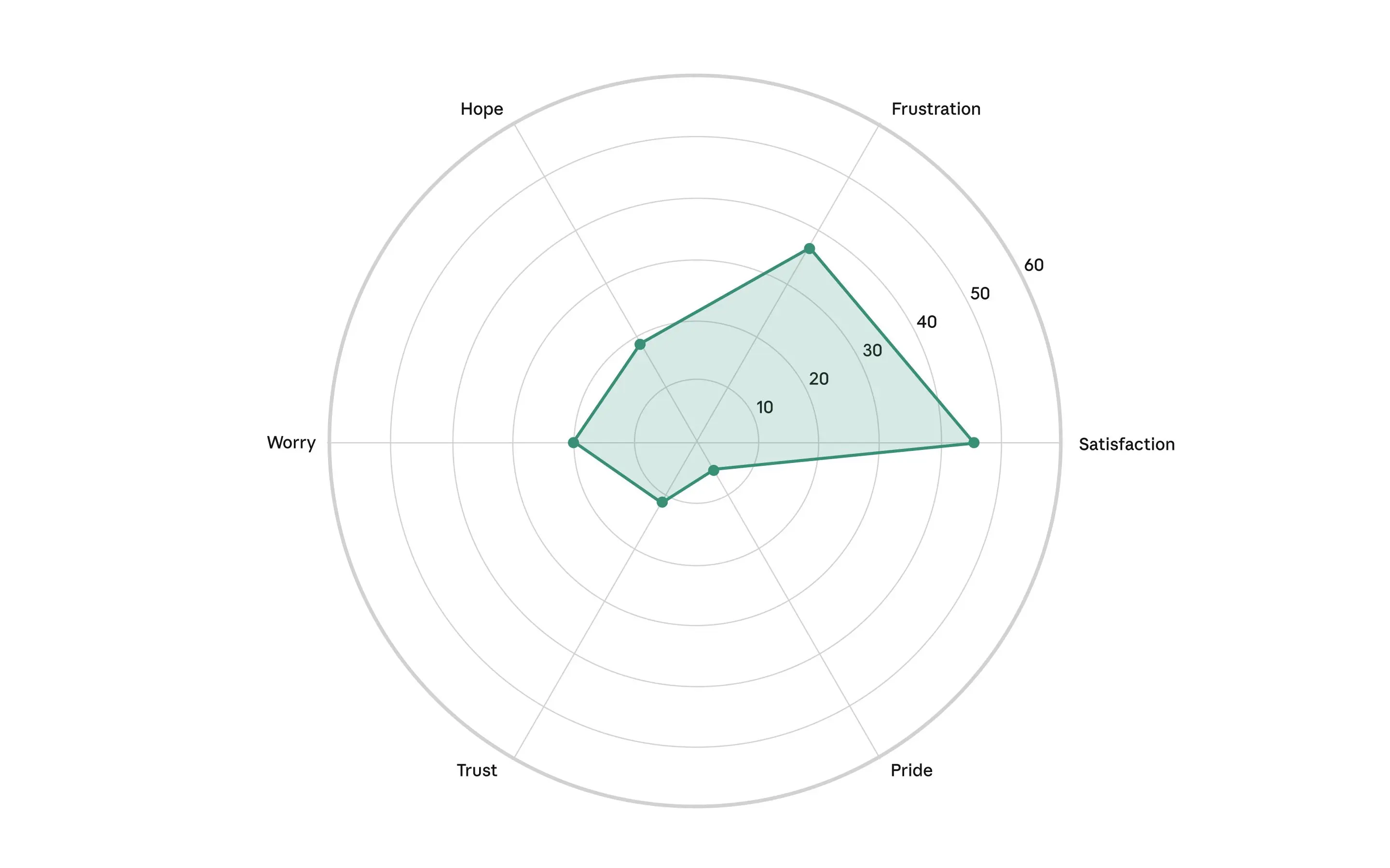

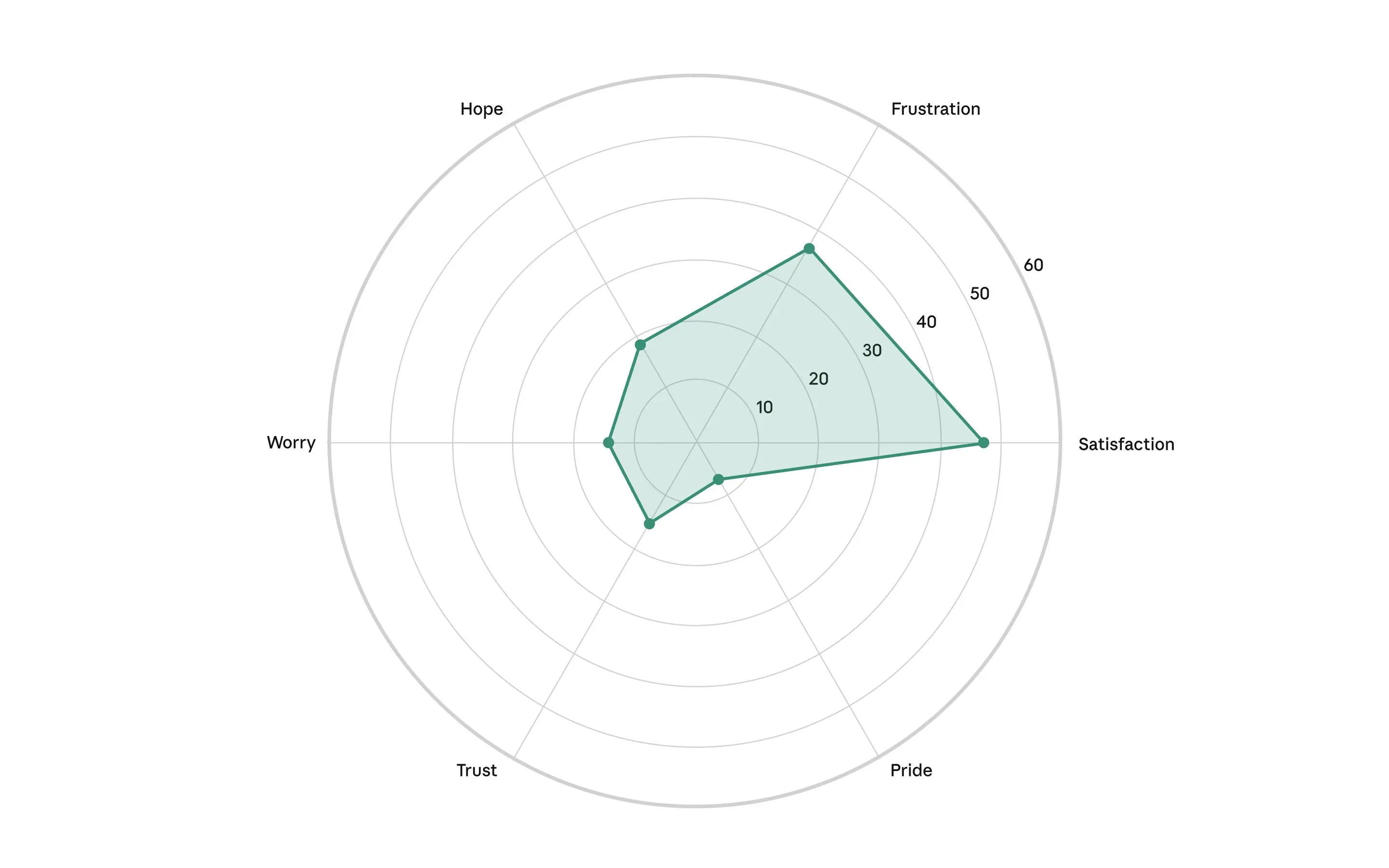

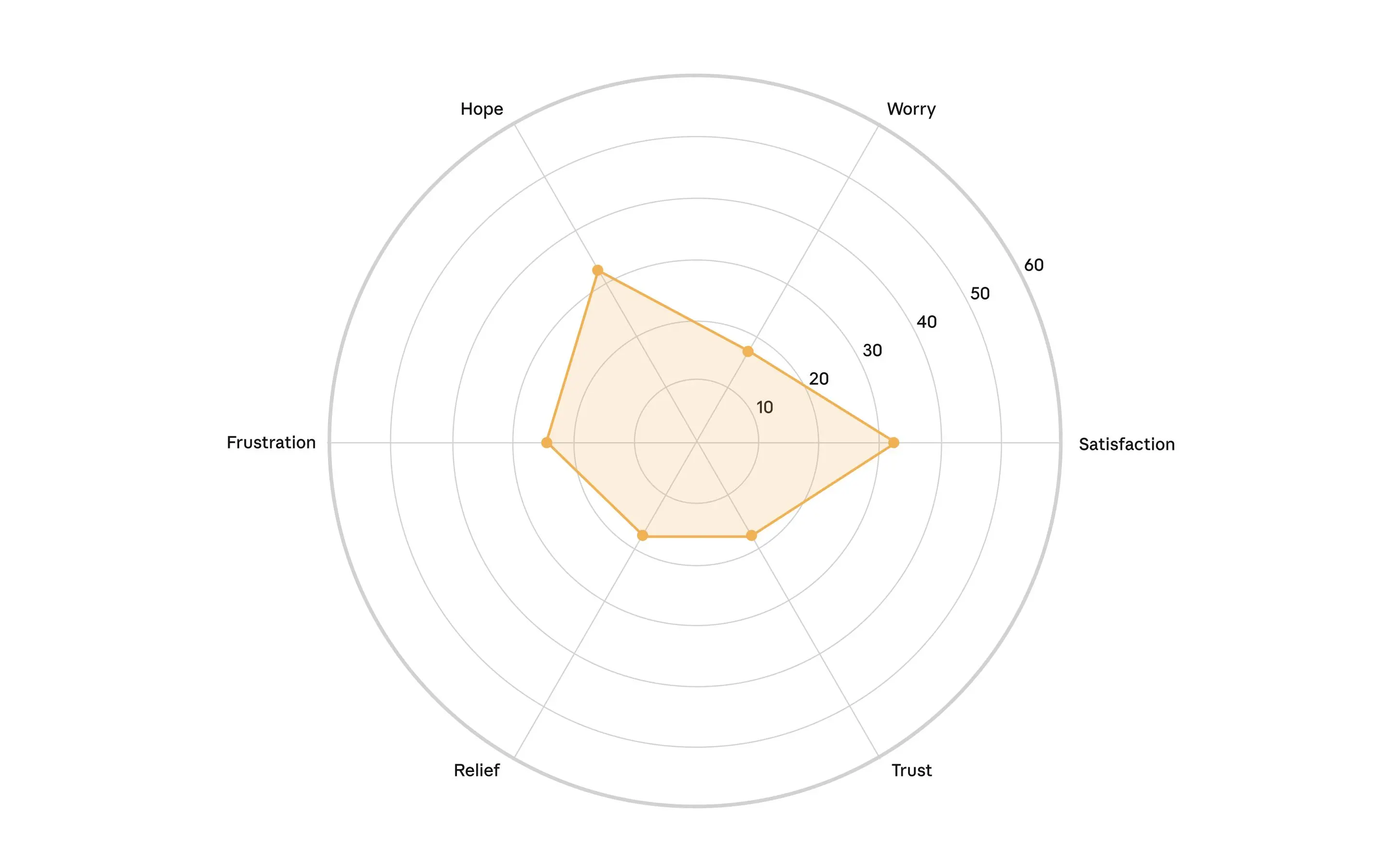

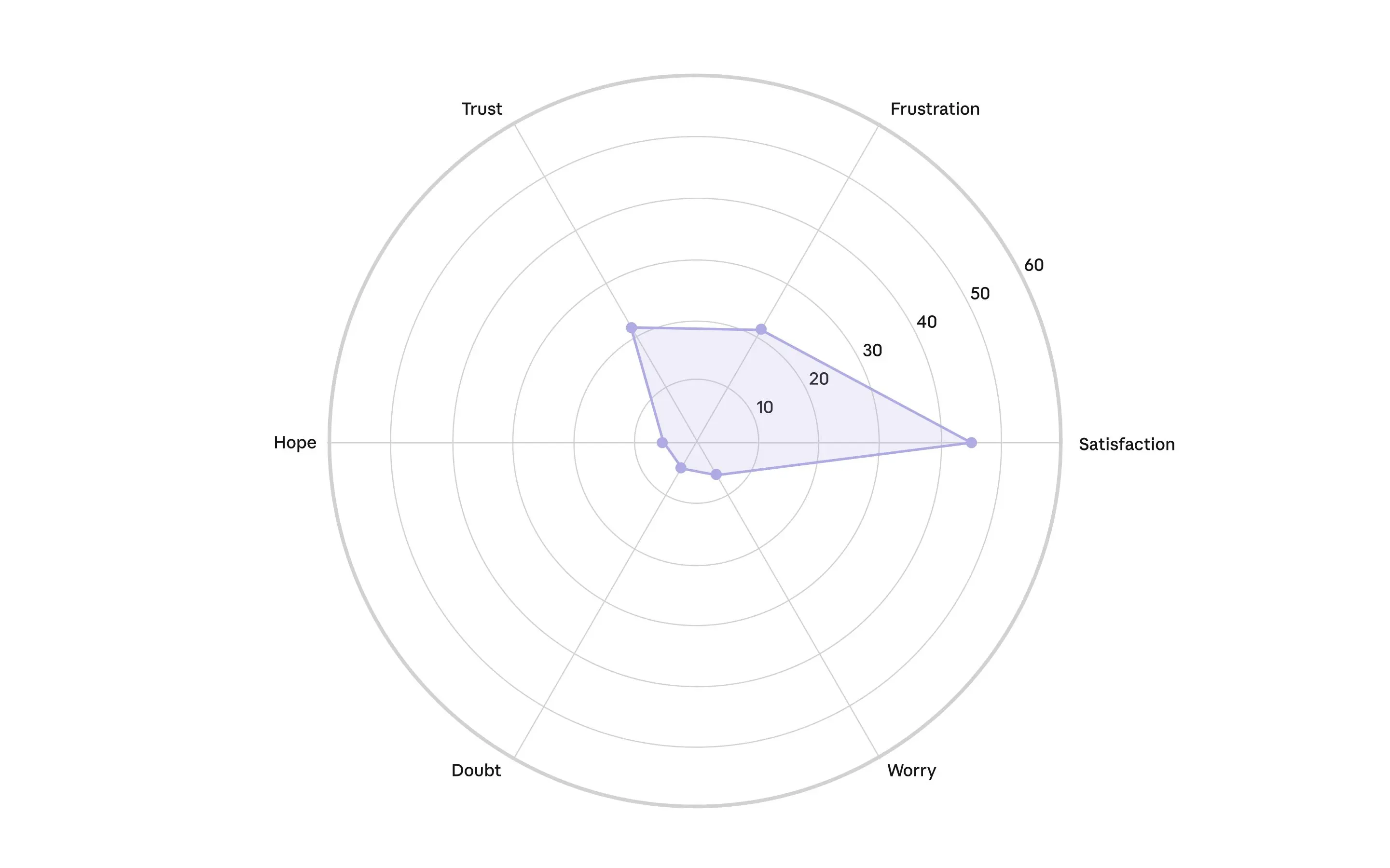

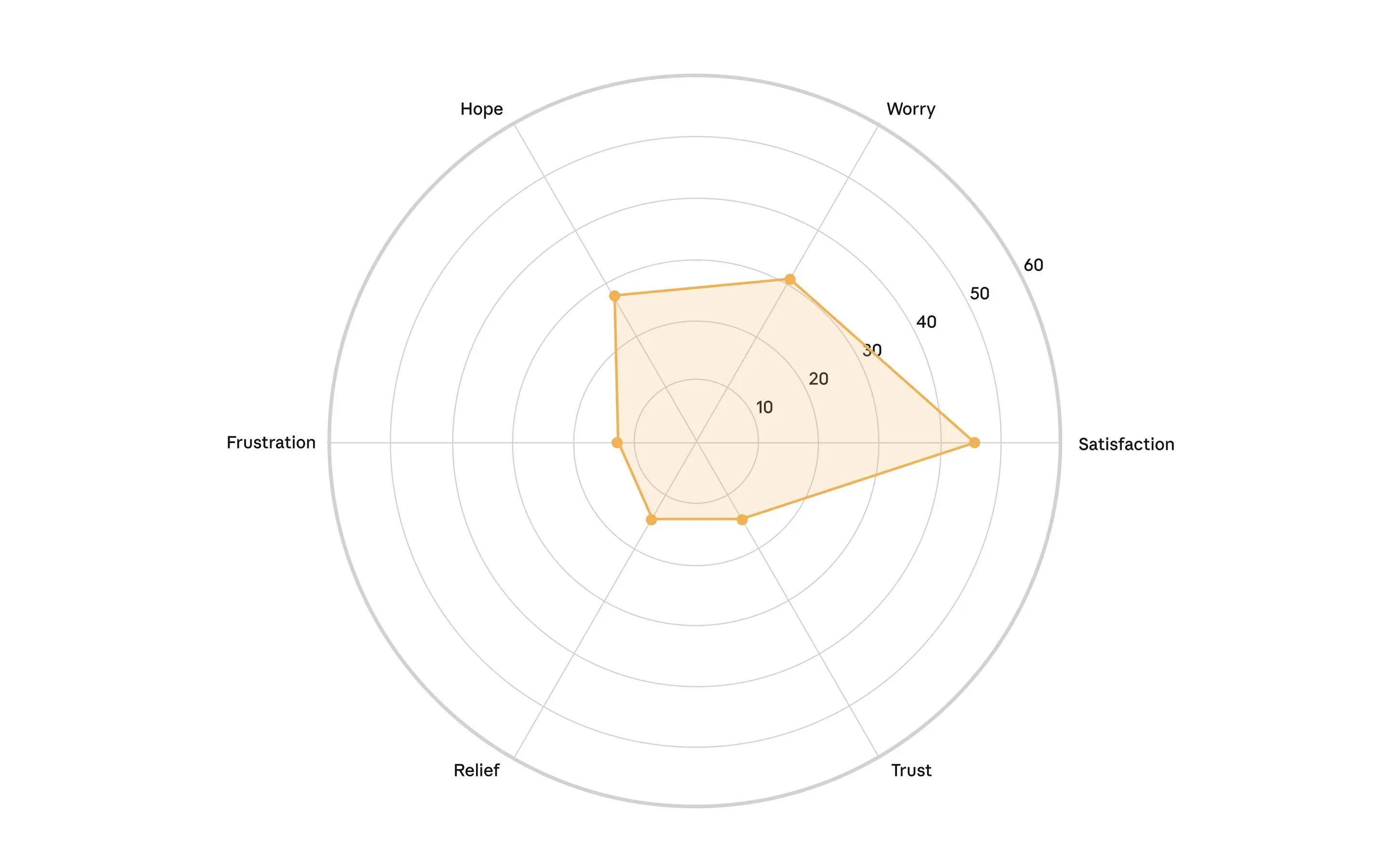

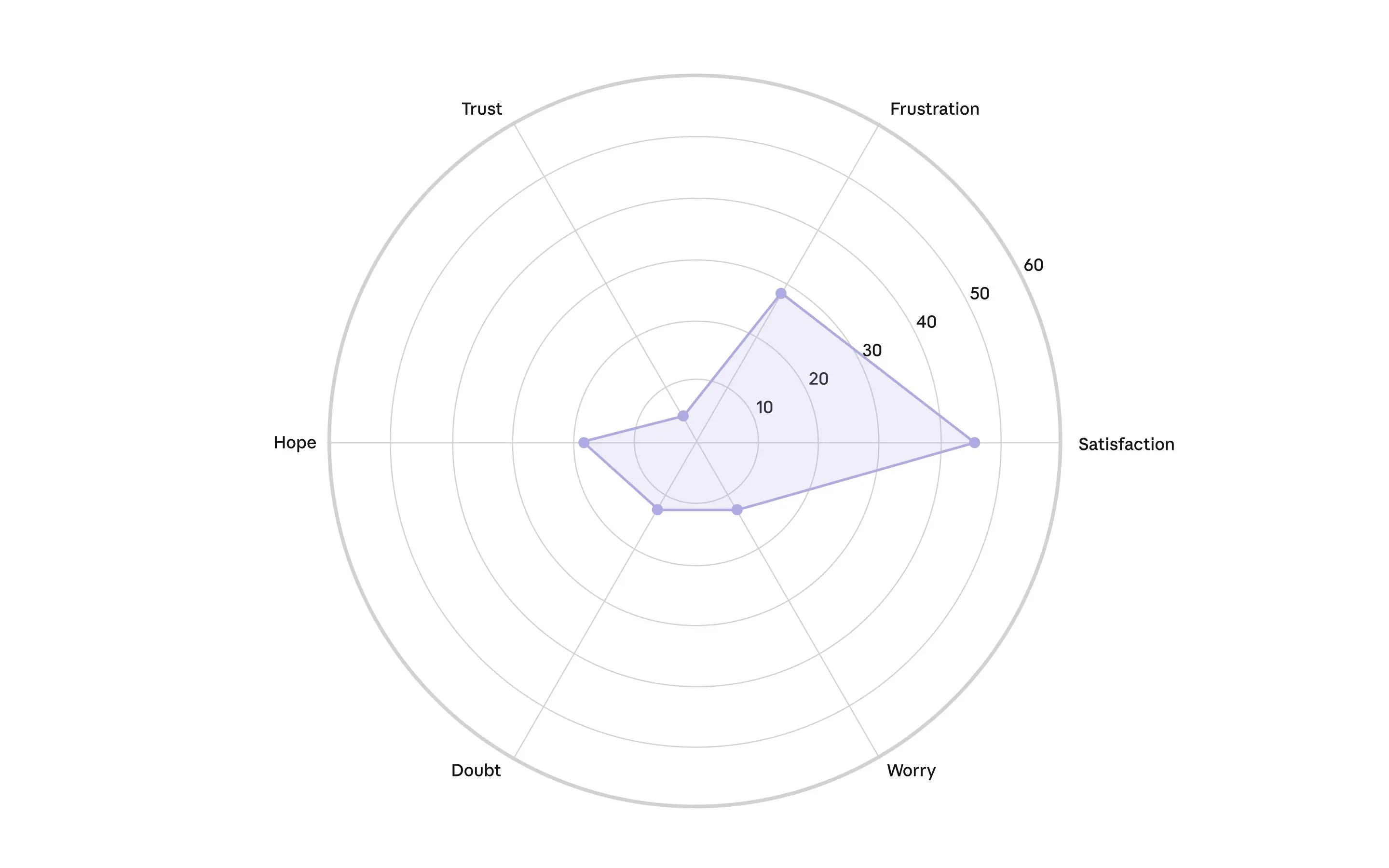

We also classified the intensity of different emotions exhibited within professionals’ interviews (see figure above). Different professions exhibited remarkably uniform emotional profiles characterized by high levels of satisfaction. However, this was coupled with frustration, suggesting professionals are finding AI useful while encountering significant implementation challenges.

Augmentation versus automation

In a previous analysis, we categorized AI uses into either augmentation (where AI collaborates with a user to perform a task), or automation (where AI directly performs tasks). In the Anthropic Interviewer data, 65% of participants described AI’s primary role as augmentative; 35% described it as automative. Notably, this differed from our latest analysis of how people use Claude, which showed a much more even split: 47% of tasks involved augmentation and 49% automation. There are multiple potential explanations for this difference:

- There could be sample differences between Anthropic Interviewer study respondents and the users in our previous study;

- People’s conversations on Claude may look more automative than they actually are—users might refine or adapt Claude’s outputs after the chat ends;

- The participants might use different AI providers for different tasks;

- Self-reported interaction styles might diverge from real-world usage;

- Professionals might perceive their AI use as more collaborative than their Claude conversation patterns indicate.

Professionals envisioned a future with both augmentation and automation—the automation of routine, administrative tasks with the maintenance of human oversight. 48% of interviewees considered transitioning their careers toward positions that focus on managing and overseeing AI systems rather than performing direct technical work.

...if I use AI and up my skills with it, it can save me so much time on the admin side which will free me up to be with the people.

A pastor said that “...if I use AI and up my skills with it, it can save me so much time on the admin side which will free me up to be with the people”. They also emphasized the importance of “good boundaries”, and avoiding becoming “so dependent on AI that I can't live without [it] or do what I'm called to do.”

A communications professional said: “I believe the majority of my job will probably be overtaken by AI one day. I think my role will eventually become focused around prompting, overseeing, training and quality-controlling the models rather than actually doing the work myself”. Professionals who were currently barred from using AI at work—for example, some lawyers, accountants, and healthcare workers—anticipated policy changes that would let them automate many tasks in the future.

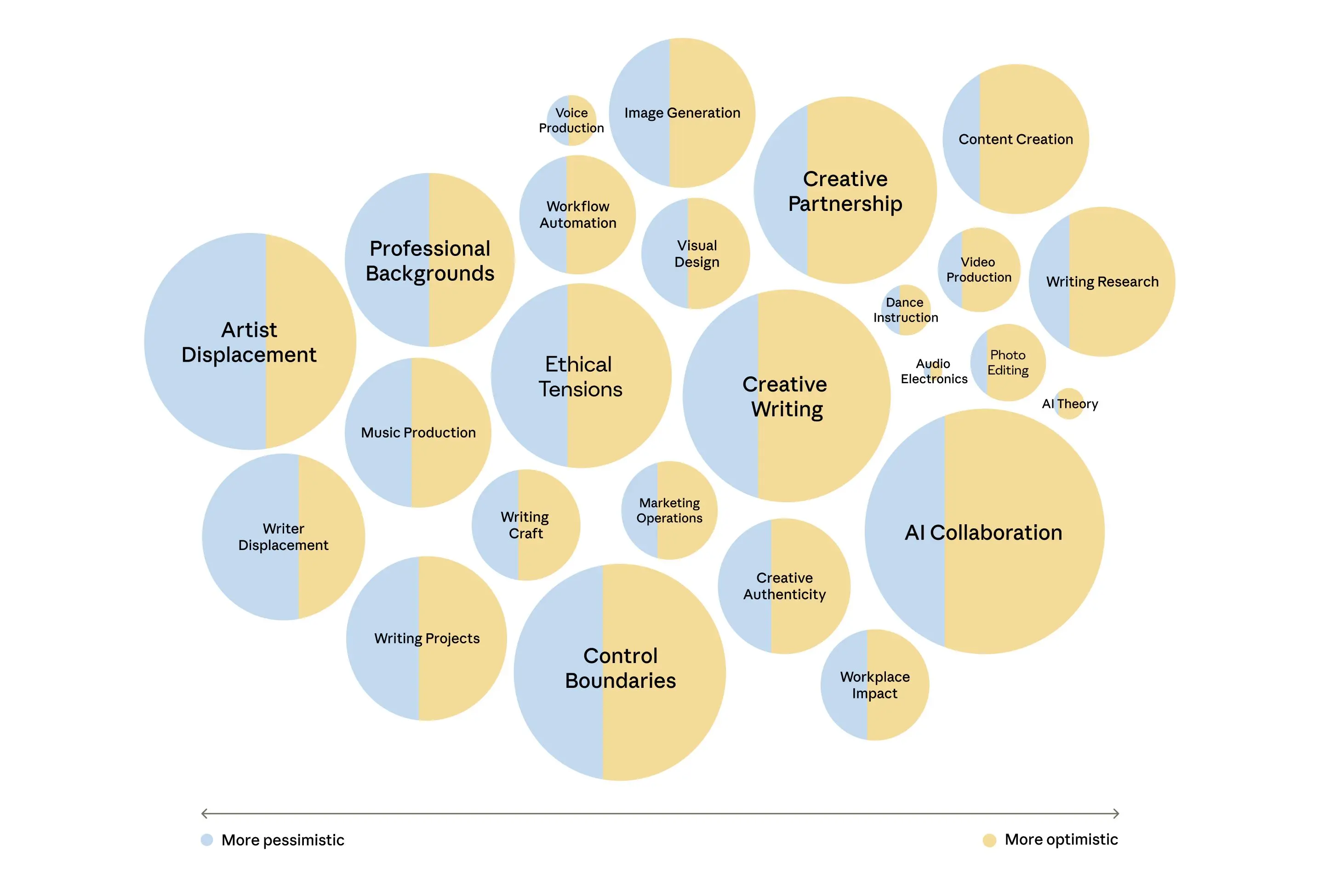

AI’s impact on creative professions

Our sample of creative professionals also reported that AI made them more productive. 97% reported that AI saved them time and 68% said it increased their work’s quality. One novelist explained “I feel like I can write faster because the research isn’t as daunting,” while a web content writer reported they’ve “gone from being able to produce 2,000 words of polished, professional content to well over 5,000 words each day.” A photographer noted how AI handled routine editing tasks—reducing turnaround time from “12 weeks to about 3”—allowing them to “intentionally make edits and tweaks that I may have missed before or not had time for.”

Similarly to the general sample, 70% of creatives mentioned trying to manage peer judgment around AI use. One map artist said: “I don't want my brand and my business image to be so heavily tied to AI and the stigma that surrounds it.”

Certain sectors of voice acting have essentially died due to the rise of AI.

Economic anxiety appeared throughout creatives’ interviews. A voice actor stated that: “Certain sectors of voice acting have essentially died due to the rise of AI, such as industrial voice acting.” A composer worried about platforms that might “leverage AI tech along with their publishing libraries [to] infinitely generate new music,” flooding markets with cheap alternatives to human-produced music. Another artist captured similar concerns: “Realistically, I’m worried I'll need to keep using generative AI and even start selling generated content just to keep up in the marketplace so I can make a living.” A creative director said: “I fully understand that my gain is another creative’s loss. That product photographer that I used to have to pay $2,000 per day is now not getting my business.” (Note that Claude does not produce images, videos, or music—participants’ expressed anxieties are therefore about AI writ large, and not specific to Claude).

All 125 participants mentioned wanting to remain in control of their creative outputs. Yet this boundary proved unstable in practice: Many participants acknowledged moments where AI drove creative decisions. One artist admitted: “The AI is driving a good bit of the concepts; I simply try to guide it… 60% AI, 40% my ideas”. A musician said: “I hate to admit it, but the plugin has most of the control when using this.”

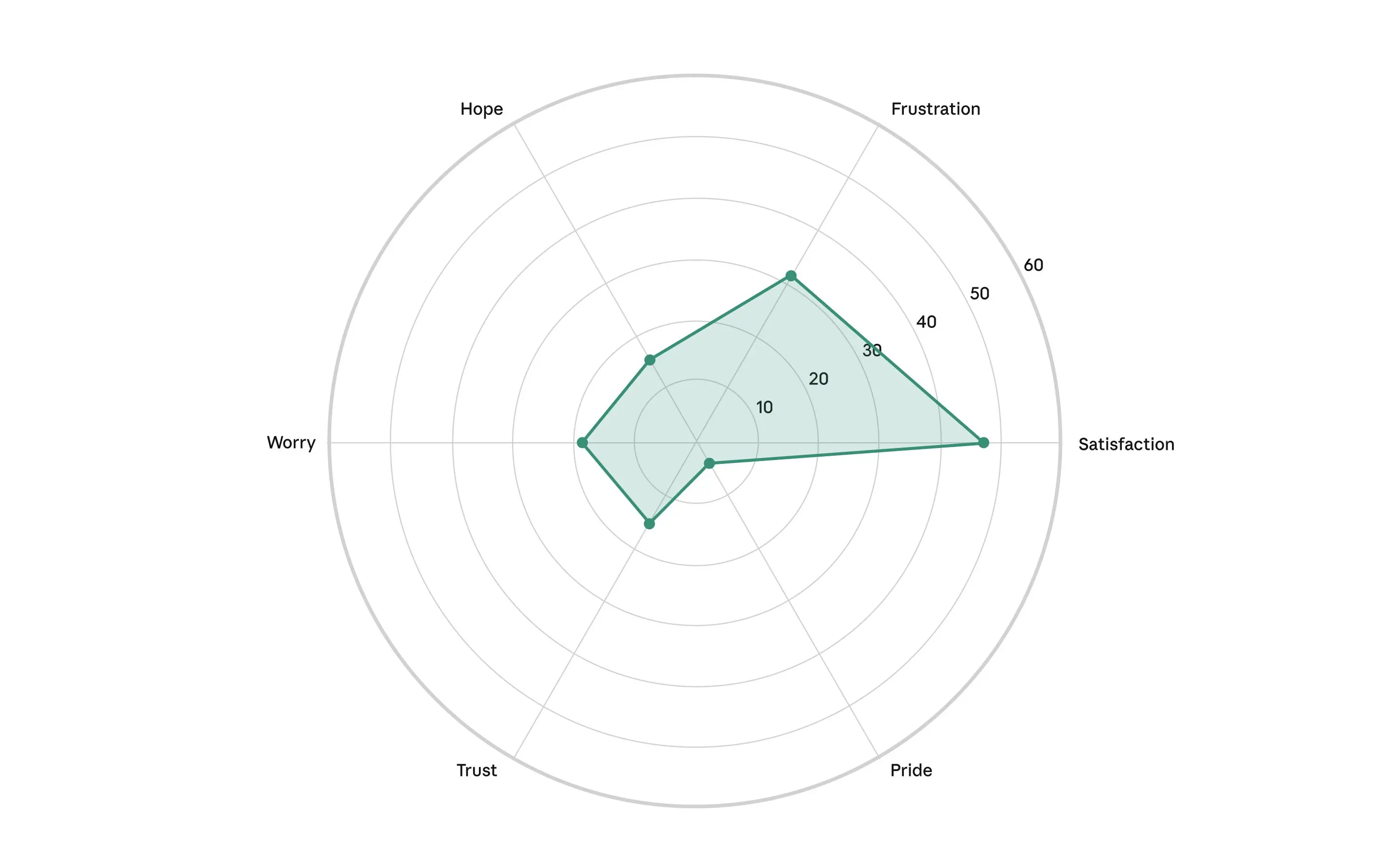

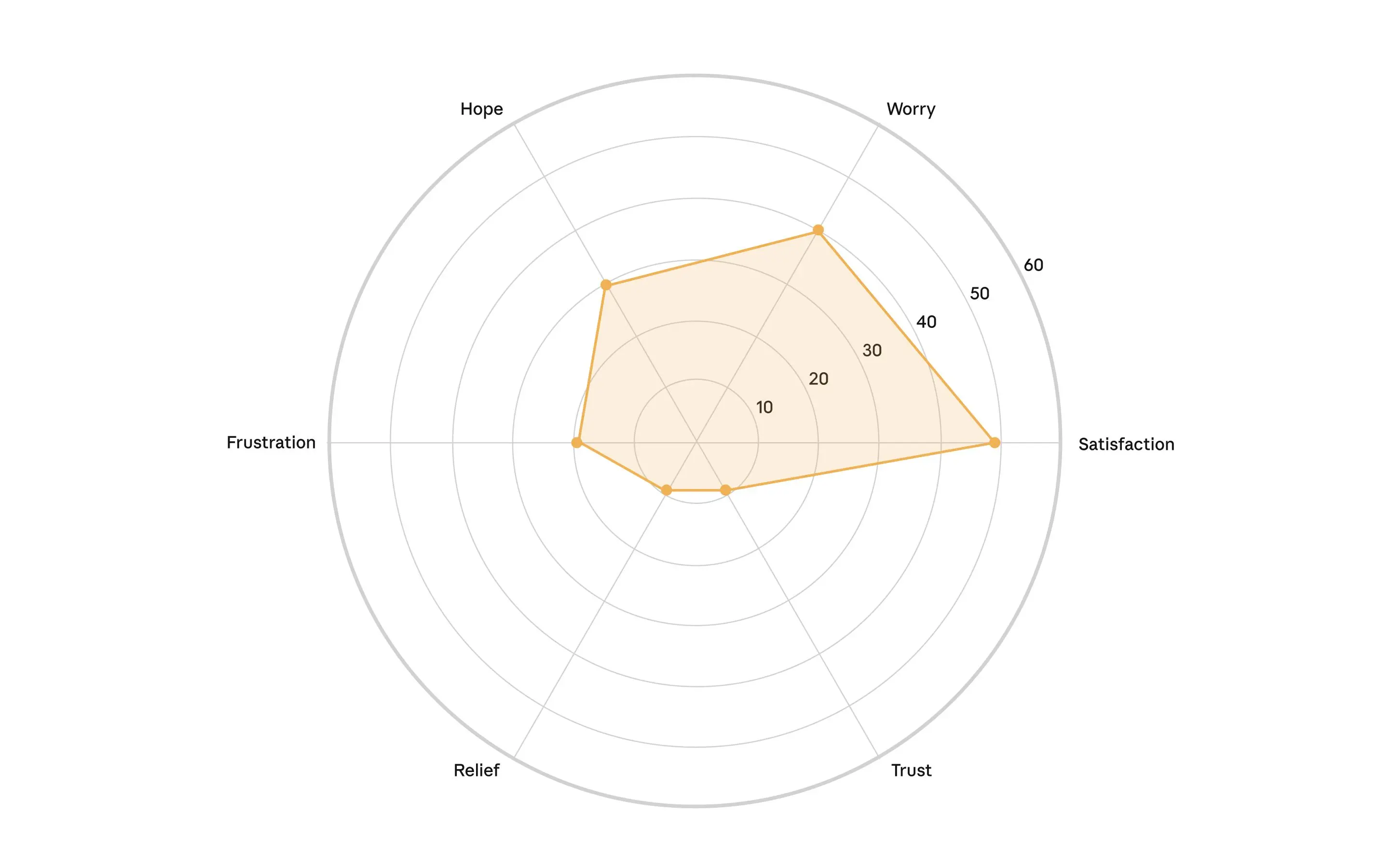

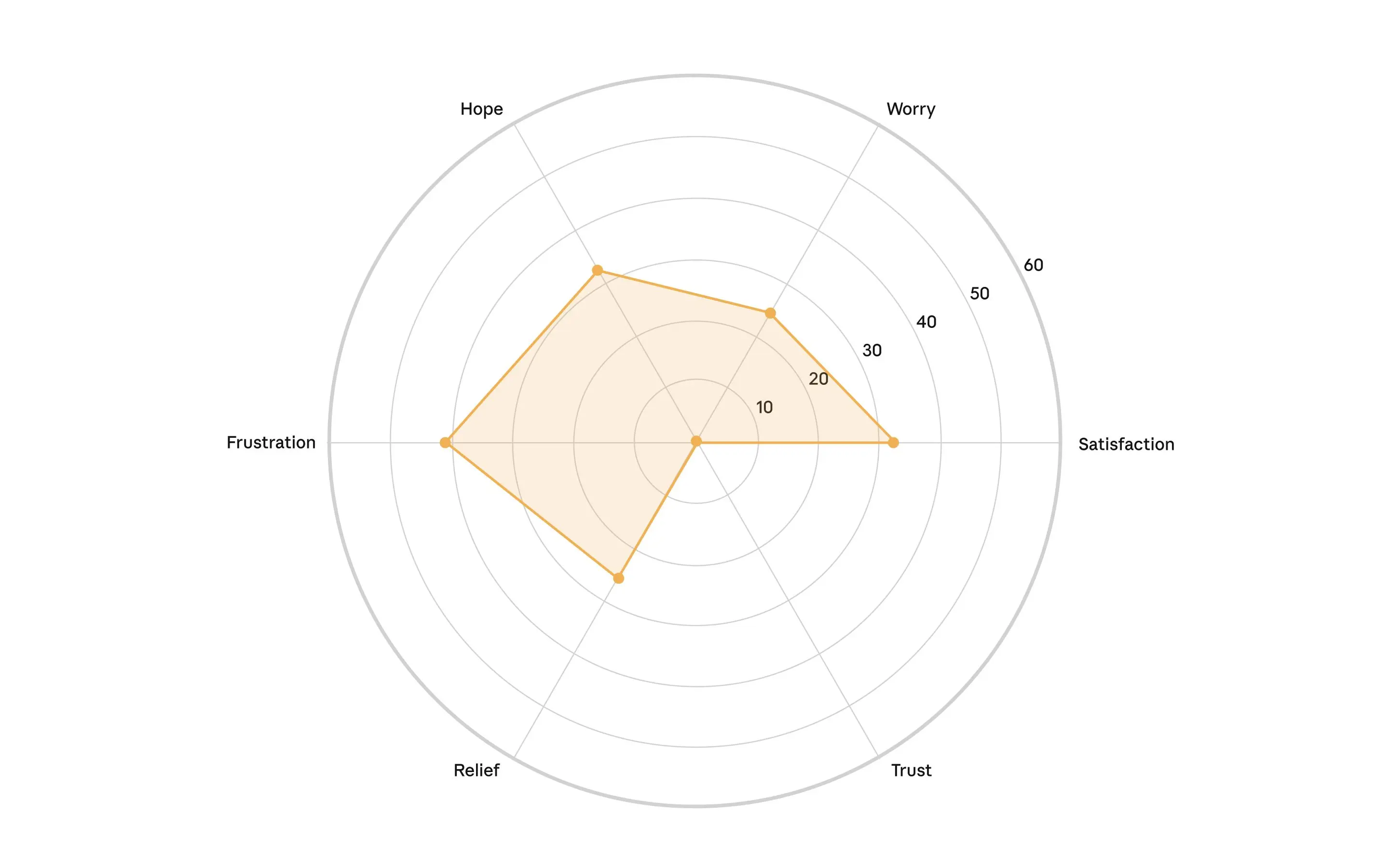

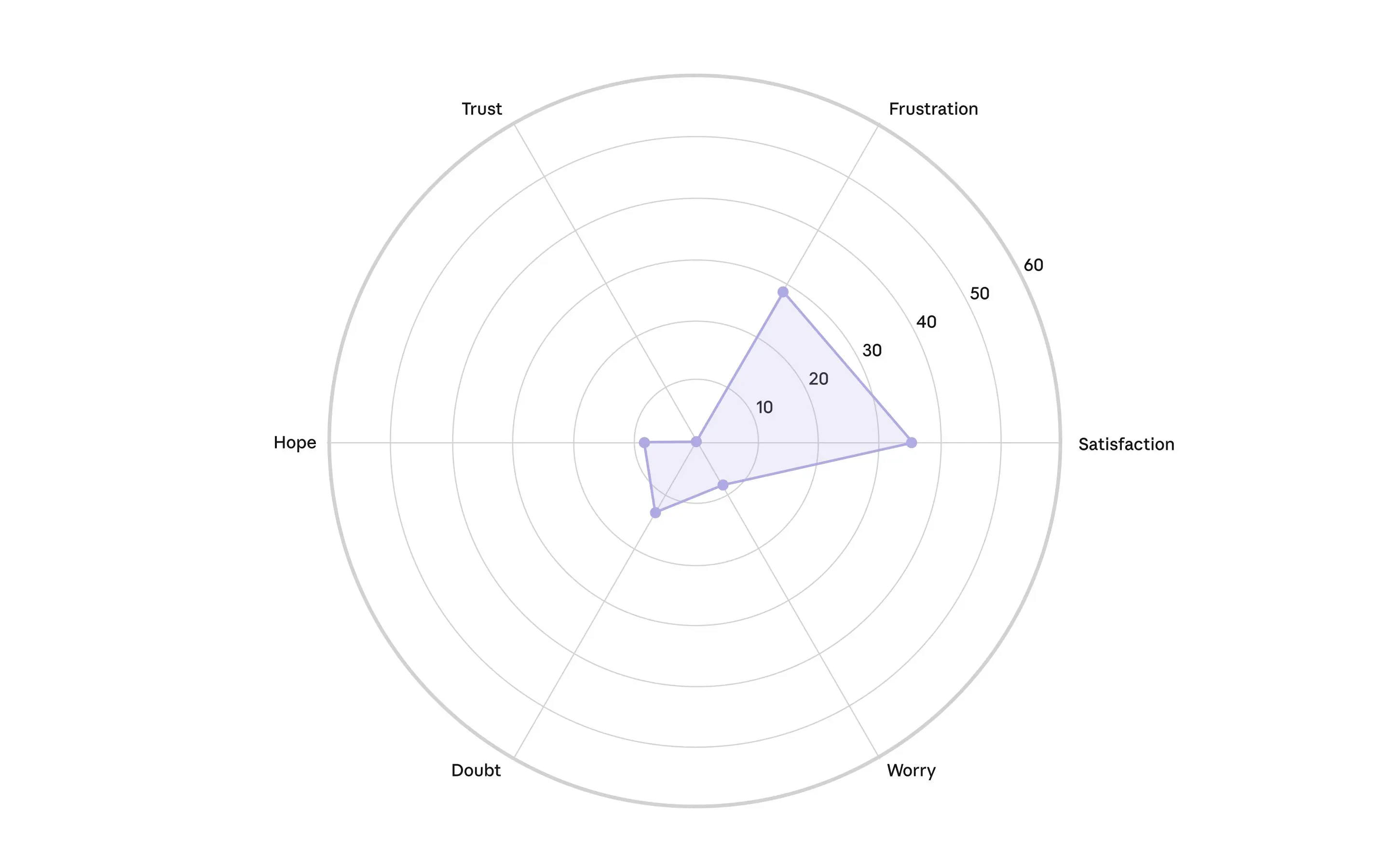

Disciplines exhibited divergent emotional profiles as seen in the figure above: game developers and visual artists reported high satisfaction, paradoxically paired with elevated worry. Designers showed an inverse pattern dominated by frustration with notably low satisfaction. Across all disciplines, trust remained consistently low, suggesting shared uncertainty about AI’s long-term implications for creative work. The tension between satisfaction and worry may highlight the position of creative professionals who simultaneously embrace AI tools while grappling with concerns about the future of human creativity. The wide dispersion across the emotional spectrum confirmed that different creative professions experienced AI integration through very different emotional lenses.

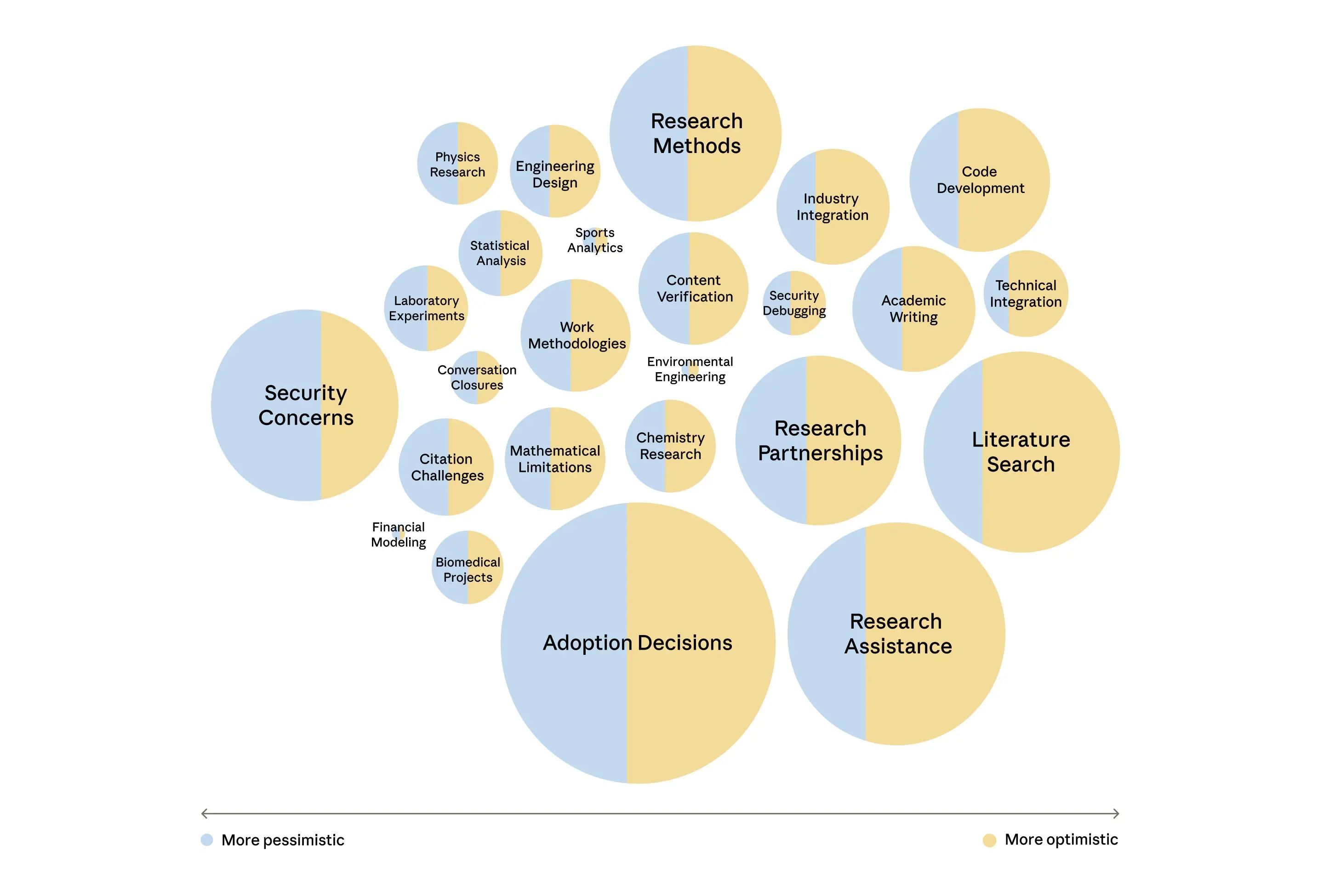

AI’s impact on scientific work

Our interviews with researchers in chemistry, physics, biology, and computational fields identified that in many cases, AI could not yet handle core elements of their research like hypothesis generation and experimentation. Scientists primarily reported using AI for other tasks like literature review, coding, and writing. This is an area where AI companies, including Anthropic, are working to improve their tools and capabilities.

Trust and reliability concerns were the primary barrier in 79% of interviews; the technical limitations of current AI systems appeared in 27% of interviews. One information security researcher noted: “If I have to double check and confirm every single detail the [AI] agent is giving me to make sure there are no mistakes, that kind of defeats the purpose of having the agent do this work in the first place.” A mathematician echoed this frustration: “After I have to spend the time verifying the AI output, it basically ends up being the same [amount of] time.” A chemical engineer noted concerns about sycophancy, explaining that: “AI tends to pander to [user] sensibilities and changes its answer depending on how they phrase a question. The inconsistency tends to make me skeptical of the AI response.”

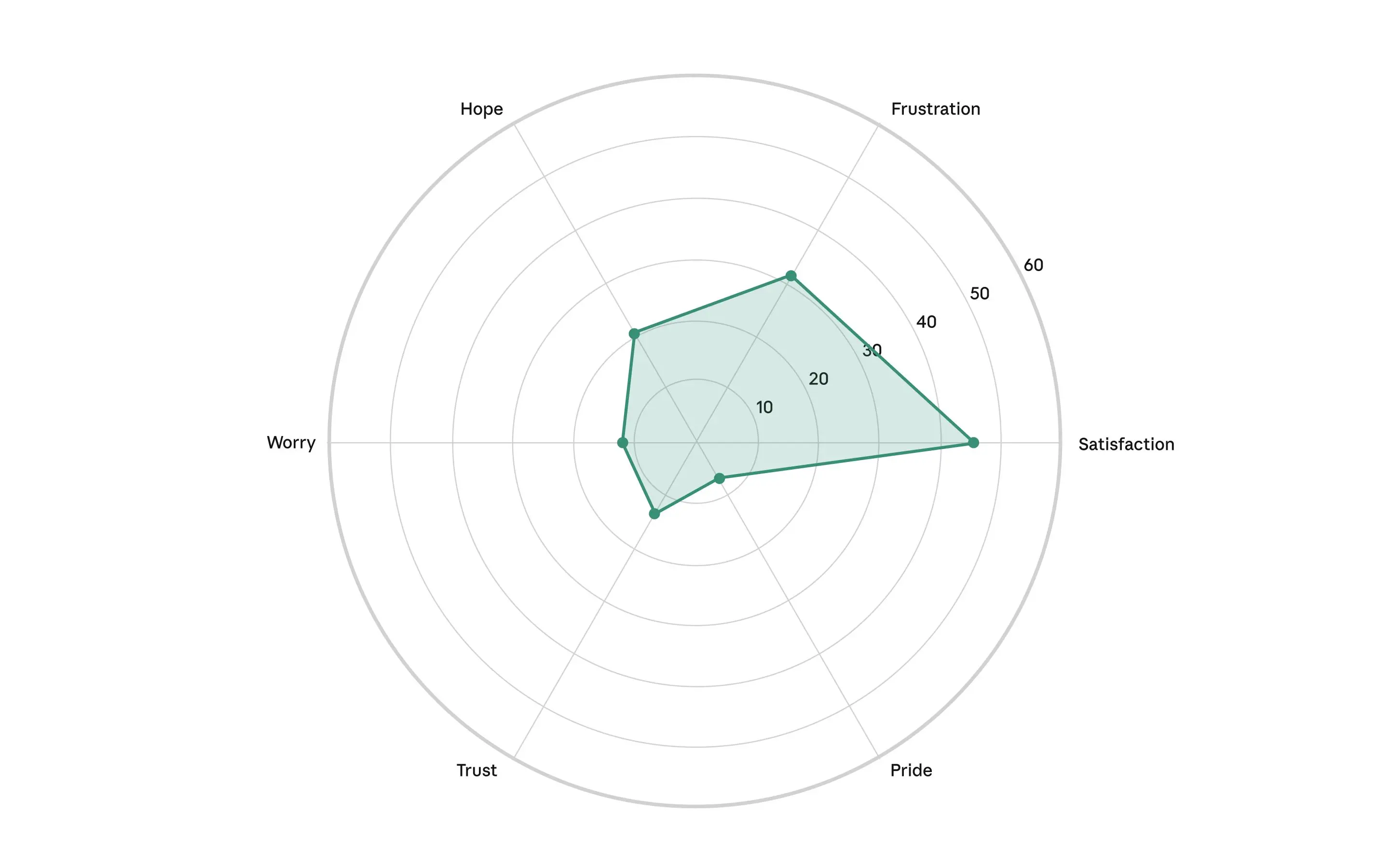

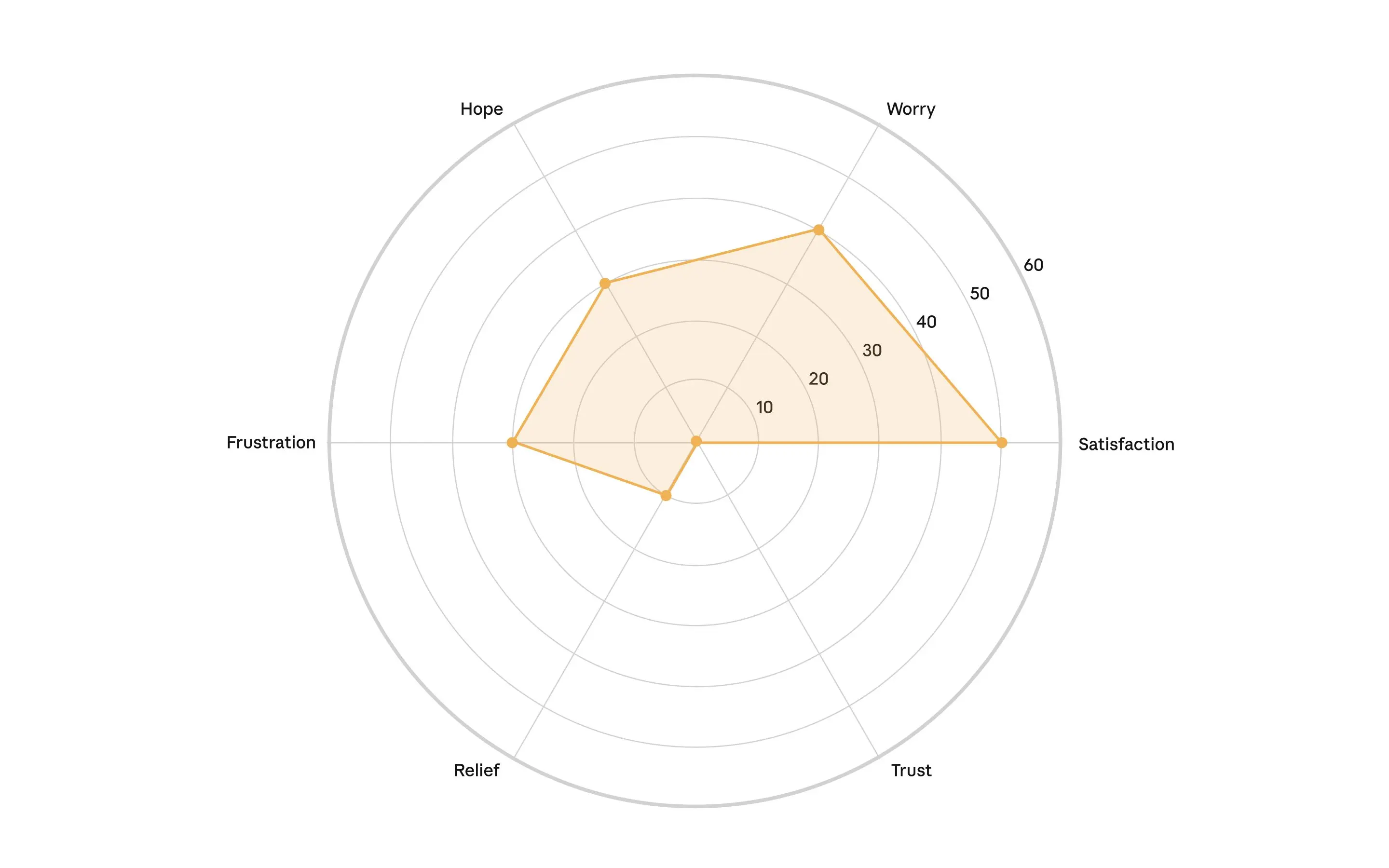

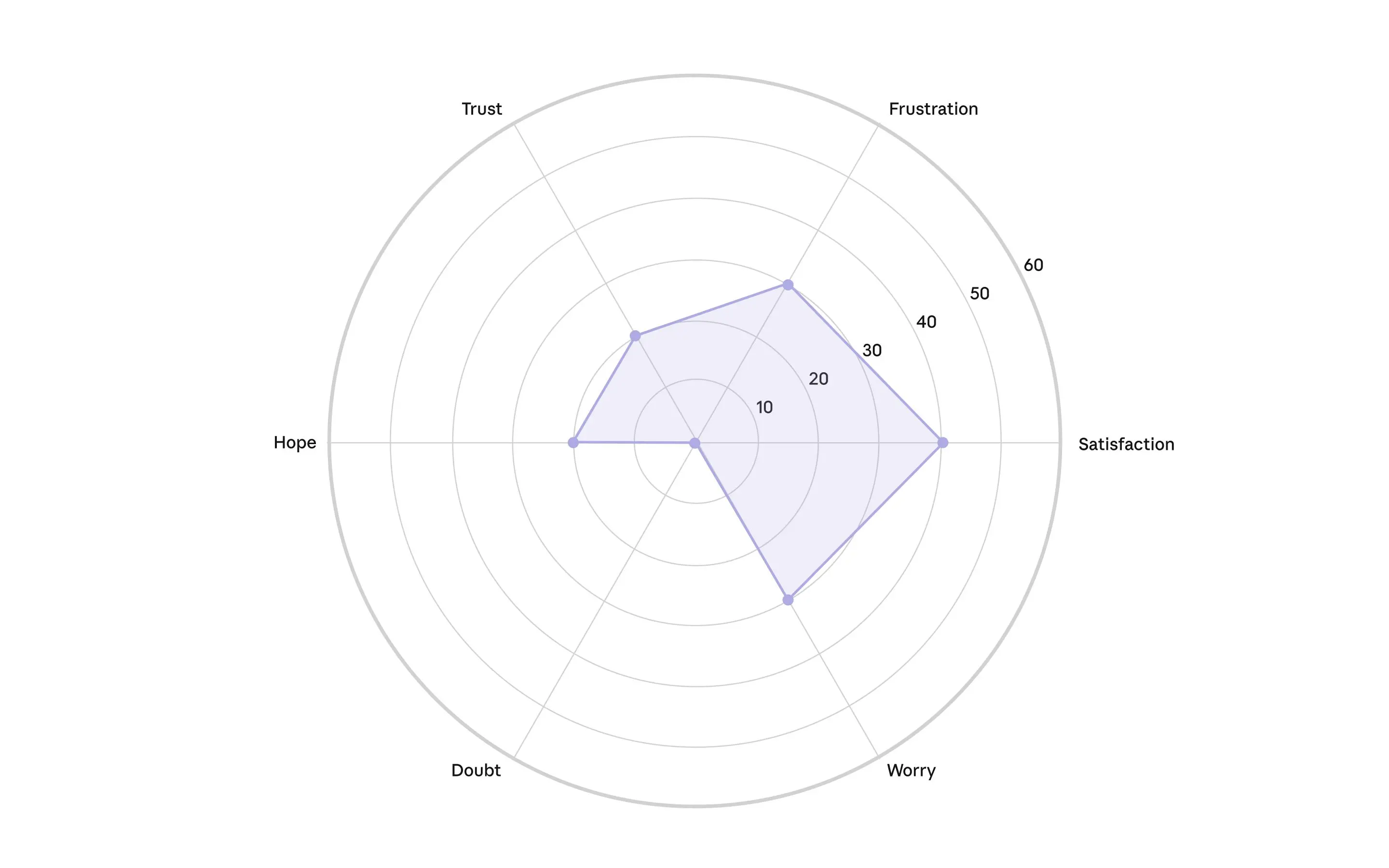

Most scientific fields reported high satisfaction, but with divergent frustration patterns: physicists and data scientists showed higher frustration, whereas chemical and mechanical engineers displayed minimal frustration. This potentially reflects differences in how computational versus experimental fields attempt to integrate AI into core research workflows: scientists whose work requires real-world interaction might not yet be trying to use AI for their core scientific experimentation. Trust remains relatively low across all fields, indicating widespread reliability concerns regardless of discipline. Unlike creative professionals who express high levels of concern about AI’s impact, scientists show relatively low worry levels. This coheres with their stated frustrations regarding AI’s ability to complete hypothesis generation and experimentation tasks.

Scientists didn’t, in general, fear job displacement due to AI. Some pointed to tacit knowledge that resists digitization, with one microbiologist explaining: “I worked with one bacterial strain where you had to initiate various steps when the cells reached specific colors. The differences in color have to be seen to be understood and [instructions are] seldom written down anywhere.” Others emphasized the inherently human nature of research decision-making, with one bioengineer stating: “Experimentation and research is also… inherently up to me”, and noted that “certain parts of the research process are unfortunately just not compatible with AI even though they are the part that would be most convenient to automate, like running experiments”.

External constraints also created barriers to AI replacement—researchers in classified environments noted that “there are a lot of ‘do's and don'ts’ with lots of security-oriented processes that must be put in place before the organization can allow us to use agentic frameworks, and even LLMs for example.” A mechanical engineer managing limited resources explained that, although “AI is good at coming up with an experimental design,” in reality “most of my research has budget/time/specimen limits so the ‘ideal’ design isn't always viable.” Nevertheless, regulatory compliance constraints, concerns about skill atrophy, and cost barriers were each brought up in less than 10% of interviews.

I would love an AI which could feel like a valuable research partner… that could bring something new to the table.

91% of scientists expressed a desire for more AI assistance in their research, even if they didn’t feel today’s products fit the bill. Roughly one-third envisioned assistance primarily with writing tasks, but the majority wanted support across all of their research: critiquing experimental design, accessing scientific databases, and running analyses. A common desire was for an AI that could produce new scientific ideas. One medical scientist said: “I wish AI could… help generate or support hypotheses or look for novel interactions/relationships that are not immediately evident for humans”. Another echoed this sentiment, saying: “I would love an AI which could feel like a valuable research partner… that could bring something new to the table.”

Looking forward

This initial test demonstrated that Anthropic Interviewer shows promise at scale—we were able to conduct 1,250 interviews with a range of professionals to understand their feelings regarding AI at work. Research with this many participants would have been expensive and time-consuming with traditional “manual” interview methods.

But the significance of Anthropic Interviewer extends beyond methodology: it fundamentally shifts what questions we can ask and answer about AI’s role in society, and how interviews about any topic can happen at this new scale. Our effort to conduct meaningful research at scale with Anthropic Interviewer is only just beginning. Previously, we only had insight into how people were using Claude within the chat window. We didn't know how people felt about using AI, what they wanted to change about their interactions with the technology, or how they envisioned AI's future role in their lives.

The findings from this initial survey provide us with new insights beyond our Economic Index work to understand how people are using AI in their workplace. We are sharing these initial findings for discussion with our Economic Advisory Council and Higher Education Advisory Board. As we continue this research, we’ll publicly share our pilot results, along with how the findings inform our future work.

Anthropic Interviewer is our latest step to center human voices in the conversation about the development of AI models—something we began with our work on Collective Constitutional AI, which gathered public perspectives to shape Claude’s behavior. These conversations can help us improve the character and training process of Claude itself as well as inform future policies that Anthropic champions and adopts. Below are some of the practical steps we’ve taken to explore partnerships with specific communities, helping us develop AI informed by their expertise:

- Creatives. We’re supporting the development of exhibitions, workshops, and events to understand how AI is augmenting creativity. We have partnerships with leading cultural institutions including the LAS Art Foundation, Mori Art Museum, and Tate, and creative communities such as Rhizome and Socratica. In addition, we are collaborating with the companies behind popular creative tools to explore how Claude can augment creatives’ work via the Model Context Protocol.

- Scientists. We’re partnering with our AI for Science grantees to understand how AI can best serve their research. Using Anthropic Interviewer, we’re gathering scientists’ perspectives on AI and their hopes for the program (we’ll also use our privacy-preserving analysis tool to assess whether their Claude conversations align with these expectations). Combining quantitative and qualitative data will help us both improve Claude for scientists and measure the impacts of our grants.

- Teachers. We’ve recently partnered with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) to reshape teacher training in an age of increasingly capable AI. This program aims to support 400,000 teachers in AI education and introduce their perspective in the development of AI systems. In addition, we previewed some findings from Anthropic Interviewer regarding how AI is transforming software engineering at Anthropic. Sharing qualitative stories about our own workplace transformation led us to find much common ground between software engineers and teachers, bringing everyone together at the same table to brainstorm what kinds of AI induced work transformations we actually want.

Using Anthropic Interviewer, we can conduct targeted research that informs specific policies, participatory research that involves different communities in conversations about AI, and regular studies that track the evolving relationship between humans and AI.

Take part

We are continuing to use Anthropic Interviewer to better understand how people envision AI’s role in their lives and work. To that end, we are launching a public pilot interview, exploring what experiences, values and needs drive people’s vision for AI’s future role in their lives.

Ready to share your perspective? You can participate in a 10-15 minute interview at this link to take part in this research. We plan to analyze the anonymized insights from this study as part of our societal impacts research and publish a report on insights from this data. For more information on this study, please see the FAQ section below.

Conclusions and limitations

Our interviews with 1,250 professionals reveal a workforce actively negotiating its relationship with AI. Our participants generally preserved tasks central to their professional identity while delegating routine work for productivity gains. Creatives embraced AI’s efficiency despite peer stigma and economic anxieties, while scientists remained selective about which research tasks they entrusted to AI.

We conducted this research to understand AI’s impact on people’s lives beyond what happens in the chat window. Like all qualitative analysis, our interpretation of these interviews reflects the questions we chose to ask and the patterns we looked for in the data. By making this large-scale dataset of interview transcripts publicly available, we hope to advance collective understanding of how human-AI relationships are evolving. And by deploying Anthropic Interviewer at scale, we can create a feedback loop between what people experience with AI and how we develop it—with the goal of building AI systems that reflect public perspectives and needs.

Limitations

Our initial use of Anthropic Interviewer has some important limitations that affect the scope and generalizability of our findings. Our findings should be interpreted as early signals of AI’s impact on work, rather than definitive conclusions about its long-term effects on professional practice and identity.

- Selection bias. Because they were engaged through crowdworker platforms, the experiences of the participants in our study might differ significantly from those of the general workforce, biasing responses toward more positive or experienced perspectives on the subject.

- Demand characteristics. Participants knew they were being interviewed by an AI system about their AI usage, which could have changed their willingness to engage, or changed the kinds of responses they gave compared to an interview with a human.

- Static analysis. We captured a snapshot of professionals’ current AI usage and attitudes, but with these data, we can’t track how these relationships develop over time, or how initial enthusiasm might change with extended use.

- Emotional analysis. As Anthropic Interview is text-only and can’t read tone of voice, facial expressions, or body language, it might miss emotional cues that affect the meaning of our interviewee’s statements.

- Self-report versus objective measures. We noted above that participants’ descriptions of their AI usage might differ from their actual practices (as has been found to be the case for smartphone use). This could be due to social desirability bias, imperfect recall, or evolving workplace norms around AI disclosure.

- Indeed, our interview data revealed key discrepancies when compared with real usage data. This gap between perception and practice reinforces the inherent ambiguity in self-reports: for example, interview responses may capture aspirational usage or social desirability effects. Understanding these discrepancies will be crucial for interpreting the findings in this kind of research.

- Researcher interpretation. Like all qualitative research, our analysis reflects our own interests and perspectives as researchers. Although we used systematic methods to identify patterns, different researchers might emphasize different aspects of these interviews or draw alternative conclusions.

- Global generalizability. Our sample primarily reflects Western-based workers, and cultural attitudes toward AI, workplace dynamics, and professional identity likely vary significantly across global contexts.

- Non-experimental research. Although many participants reported productivity gains and quality improvements, we cannot determine whether AI usage directly caused these outcomes or the extent to which other factors contributed.

Contributions and acknowledgements

Kunal Handa led the project, designed and prototyped Anthropic Interviewer, executed the surveys, interviews, and data analysis, plotted figures, and wrote the blog post. Michael Stern led the implementation of Anthropic Interviewer within Claude.ai, managed the project timeline, and provided feedback throughout. Saffron Huang led the public pilot of Anthropic Interviewer. Jerry Hong led the visual design of Anthropic Interviewer and contributed to technical figures. Esin Durmus contributed to experimental design and provided key feedback. Miles McCain co-led implementation of technical infrastructure underlying prototypes of Anthropic Interviewer. Grace Yun, AJ Alt, and Thomas Millar implemented Anthropic Interviewer within Claude.ai and provided the technical infrastructure necessary for the public pilot. Alex Tamkin provided key feedback on early iterations of the project. Jane Leibrock contributed to all methodology for Anthropic Interviewer. Stuart Ritchie contributed to the framing and writing of the blog post. Deep Ganguli provided critical research guidance, feedback, and organizational support. All authors provided detailed guidance and feedback throughout.

Additionally, we thank Sally Aldous, Drew Bent, Shan Carter, Jack Clark, Miriam Chaum, Jake Eaton, Matt Galivan, Savina Hawkins, Sarah Heck, Hanah Ho, Mo Julapalli, Matthew Kearney, Mike Krieger, Chelsea Larsson, Joel Lewenstein, Jennifer Martinez, Wes Mitchell, Jared Mueller, Christopher Nulty, Adam Pearce, Sarah Pollack, Ankur Rathi, Drew Roper, David Saunders, Kevin Troy, Molly Villagra, Brett Wittmershaus, and Casey Yamaguma for their helpful ideas, discussion, feedback, and support. We also appreciate the comments, discussion, and feedback from Matthew Conlen, Deb Roy, and Diyi Yang.

Citation

If you’d like to cite this post you can use the following Bibtex key:

@online{handa2025interviewer,

author = {Kunal Handa and Michael Stern and Saffron Huang and Jerry Hong and Esin Durmus and Miles McCain and Grace Yun and AJ Alt and Thomas Millar and Alex Tamkin and Jane Leibrock and Stuart Ritchie and Deep Ganguli},

title = {Introducing Anthropic Interviewer: What 1,250 professionals told us about working with AI},

date = {2025-12-04},

year = {2025},

url = {https://anthropic.com/research/anthropic-interviewer},

}Appendix

Participant experience with Anthropic Interviewer

After the interviews, we surveyed participants on their interview experience. We asked: (1) How satisfied were you with this conversation?, (2) How well did this conversation capture your thoughts on {the domain}? (both on a 1-7 Likert scale), and (3) Would you recommend this interview format to others? (yes/no).

We found that participants were remarkably positive about Anthropic Interviewer. 97.6% of participants rated their satisfaction as 5 or higher, with 49.6% giving the highest rating. Similarly, 96.96% felt the conversation captured their thoughts well (5-7 rating). 99.12% of participants said they would recommend this interview format to others.

Sharing your perspective: FAQ

1. How do we access the study?

Starting today, if you are a Free, Pro, or Max Claude.ai subscriber who signed up prior to two weeks ago, you might notice a pop-up in Claude.ai asking you to participate. You can access it at: https://claude.ai/interviewer. The study will be open for a week.

2. What will this study ask me?

We will use Anthropic Interviewer to ask you about your vision for AI's role in your life, what experiences, values, and needs shape this, as well as what might help or hinder that vision.

3. How will you use the data?

We will analyze the insights from this study as part of our Societal Impacts research, publish our findings, and use this to improve our models and services in a way that reflects what we've learned. The data we collect through this study will be treated as Feedback and will be processed according to our Privacy Policy. We may also include anonymized responses in published findings. Learn more.

4. Why don’t I see the Anthropic Interviewer invitation in Claude.ai?

The interview is only available for existing Claude.ai Free, Pro, and Max users who signed up 2+ weeks ago.

If you have questions, reach out via the message icon in the lower right corner of our Help Center.

Related content

An update on our model deprecation commitments for Claude Opus 3

Read moreThe persona selection model

Read moreAnthropic Education Report: The AI Fluency Index

We tracked 11 observable behaviors across thousands of Claude.ai conversations to build the AI Fluency Index — a baseline for measuring how people collaborate with AI today.

Read more