FOUR HUNDRED METERS on MARS

The first AI-planned drive

on another planet.

Exploring new planets means that you’re always operating in the past. It takes about twenty minutes for a signal to reach a Mars rover from Earth; by the time a new instruction arrives, the rover will already have acted on the previous one.

But on December 8 and 10, 2025, the commands that were sent to NASA’s Perseverance Rover looked like something from the future. That’s because, for the first time ever, they’d been written by an AI.

Specifically, they were written by Anthropic’s AI model, Claude. Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) used Claude to plot out the route for Perseverance to navigate an approximately four-hundred-meter path through a field of rocks on the Martian surface.

Because of the delay in the signal to the rover, operators can’t micromanage where it drives. They plan a route, send it, and only later see the results. Until now, human experts have always been the ones to do that planning. This time, Claude lent a hand.

Four hundred meters isn’t far: it’s one lap of a running track. But it’s a start. Claude—the same AI model that people use to draft emails, build software apps, and analyze their company’s finances—is now helping humanity explore other worlds.

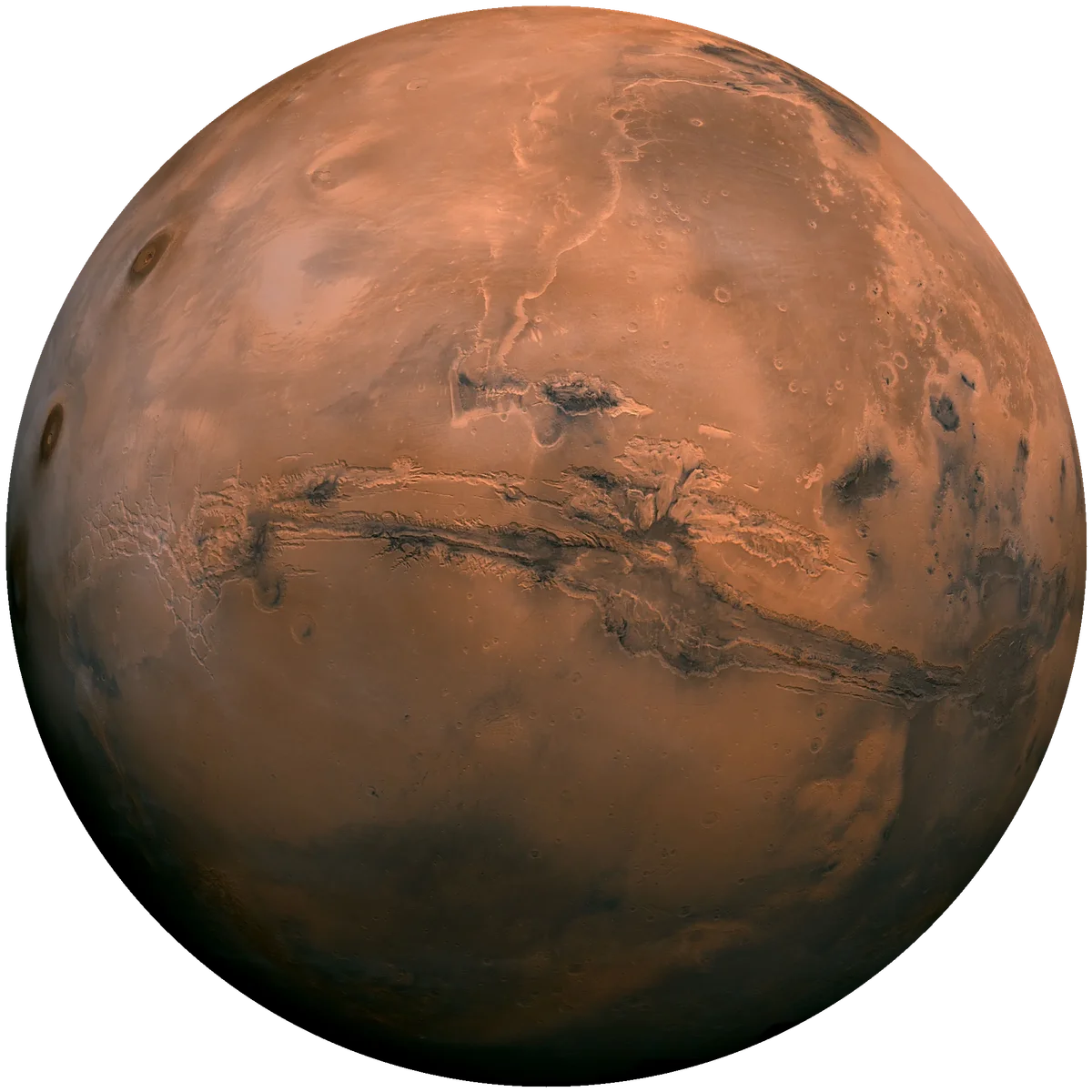

The Perseverance Rover—a car-sized robot bristling with cameras and scientific equipment—has been active on Mars since it landed in February 2021. Its mission is to characterize the planet’s geology and past climate, collecting samples of Martian rock and regolith (broken rocks and dust) and paving the way for human exploration of the Red Planet. Another of its key objectives is astrobiological in nature: its landing site, the forty-five-kilometer-wide Jezero crater, was chosen because of the evidence that once, billions of years ago, it contained water—water that might have supported microbial life. So far, the rover has discovered tantalizing hints of what might be ancient biology on Mars.

But driving on the Martian surface is hardly trivial. Every rover drive needs to be carefully planned, lest the machine slide, tip, spin its wheels, or get beached. So ever since the rover landed, its human operators have painstakingly laid out waypoints—they call it a “breadcrumb trail”—for it to follow, using a combination of images taken from space and the rover’s onboard cameras. Once it’s drawn up, the plan is transmitted across the 362 million kilometers between Earth and Mars using the Deep Space Network. Having received the signals, the rover embarks on its trip.

This is high-stakes work. In 2009, the Spirit rover, one of the forebears of Perseverance, drove into a sand trap and never moved again.

All this meticulous planning is time-consuming. Perseverance has an AutoNav system that helps it steer around obstacles between the waypoints, but it only sees things from the rover’s own perspective and can’t plan too far ahead.

JPL’s engineers tested whether Claude could save them some of that laborious work by helping to plan Perseverance’s route—and do so with the same level of accuracy as a human operator. They set up a process in Claude Code to delegate the waypoint-setting to the AI.

Claude didn’t do this with a single prompt. Instead, the model needed context before it could effectively plot the waypoints. The JPL engineers gathered together the data and experience they’d gained from years of driving the rover, and provided it to Claude Code. With all this extra information, Claude used its coding skills to write commands in Rover Markup Language—the bespoke, XML-based programming language originally developed for the Mars Exploration Rover mission.

Using its vision capabilities to analyze the overhead images, Claude planned Perseverance’s breadcrumb trail point by point for sol 1707 and sol 1709 (a sol is a Martian day; these were the near-equivalent of December 8 and 10 on Earth). It strung together ten-meter segments into a path, then iterated to refine the waypoints—critiquing its own work and suggesting revisions.

As with any AI output, it’s important to check Claude’s work. The waypoints drawn by Claude were run through a simulation that Perseverance uses every day to confirm the accuracy of the commands: over 500,000 variables were modeled to check the projected positions of the rover and predict any hazards along its route.

When the JPL engineers reviewed Claude’s plans, they found that only minor changes were needed. For instance, ground-level camera images (which Claude hadn’t seen) gave a clearer view of sand ripples on either side of a narrow corridor; the rover drivers elected to split the route more precisely than Claude had at this point. But otherwise, the route held up well. The plans were sent to Mars, and the rover successfully traversed the planned path.

Over 500,000 variables were modeled to check the projected positions of the rover and predict any hazards along its route.

The engineers estimate that using Claude in this way will cut the route-planning time in half, and make the journeys more consistent. Less time spent doing tedious manual planning—and less time spent training—allows the rover’s operators to fit in even more drives, collect even more scientific data, and do even more analysis. It means, in short, that we’ll learn much more about Mars.

Claude’s role in the Perseverance mission is in many ways just a test run for what comes next.

The kinds of autonomous capabilities that Claude showed on the Mars rover drive—quickly understanding novel situations, writing code to operate complex instruments, making smart decisions without too much hand-holding from its operators—are exactly those that’ll prove useful on longer and more ambitious space missions.

NASA’s upcoming Artemis campaign aims to send humans back to the Moon, and to eventually establish a US-led base on the lunar south pole. Doing so will involve overcoming countless engineering challenges—and just like on Mars, using resources efficiently will be the watchword.

Just as Claude can apply its intelligence to the range of rather more sublunary tasks we carry out on Earth, developing a general AI assistant that’s versatile and reliable enough to help with everything from mapping lunar geology to monitoring the astronauts’ life-support systems will be a force multiplier for NASA missions to the Moon and Mars.

NASA’s upcoming Artemis campaign aims to send humans back to the Moon, and to eventually establish a US-led base on the lunar south pole.

Even further in the future, autonomous AI systems could help probes explore ever more distant parts of the solar system. Such missions would present fiendish technical problems: solar power would become less and less viable; the delay on sending signals from Earth could stretch to hours; and the pressure, temperature, and radiation of the destinations would conspire to render a robotic explorer’s lifetime far riskier—and far shorter.

“Autonomous AI systems could help probes explore ever more distant parts of the solar system.”

Claude’s four-hundred meter drive on Mars provides the first glimmer that we might be able to solve those problems, and build a future full of truly autonomous machines that can make fast, adaptive, efficient decisions without waiting for human input. A future where one day our probes might visit moons like Europa or Titan, descend through their icy shells, and chart their own course through the dark oceans below.