Agentic coding benchmarks like SWE-bench and Terminal-Bench are commonly used to compare the software engineering capabilities of frontier models—with top spots on leaderboards often separated by just a few percentage points. These scores are often treated as precise measurements of relative model capability and increasingly inform decisions about which models to deploy. However, we’ve found that infrastructure configuration alone can produce differences that exceed those margins. In internal experiments, the gap between the most- and least-resourced setups on Terminal-Bench 2.0 was 6 percentage points (p < 0.01).

Static benchmarks score a model's output directly—the runtime environment doesn’t factor into the result. Agentic coding evals are different: models are given a full environment where they write programs, run tests, install dependencies, and iterate over multiple turns. The runtime is no longer a passive container, but an integral component of the problem-solving process. Two agents with different resource budgets and time limits aren't taking the same test.

Eval developers have begun accounting for this. Terminal-Bench 2.0, for instance, specifies recommended CPU and RAM on a per-task basis in their latest 2.0 release. However, specifying resources isn't the same as enforcing them consistently. Moreover, we discovered that enforcement methodology can change what the benchmark ends up actually measuring.

How we got here

We run Terminal-Bench 2.0 on a Google Kubernetes Engine cluster. While calibrating the setup, we noticed our scores didn't match the benchmark’s official leaderboard, and infra error rates were surprisingly high: as many as 6% of tasks were failing because of pod errors, most of which were unrelated to the model’s ability to solve the tasks.

The discrepancy in scores came down to enforcement. Our Kubernetes implementation treated the per-task resource specs as both a floor and a hard ceiling: each container was guaranteed the specified resources but killed the moment it exceeded them. Container runtimes enforce resources via two separate parameters: a guaranteed allocation—the resources reserved up front—and a hard limit at which the container is killed. When these are set to the same value, there's zero headroom for transient spikes: a momentary memory fluctuation can OOM-kill a container that would otherwise have succeeded. To account for this, Terminal-Bench’s leaderboard uses a different sandboxing provider, whose implementation is more lenient, allowing temporary overallocation without terminating the container in order to favor infrastructural stability.

This finding raised a larger question: how much does resource configuration impact evaluation scores?

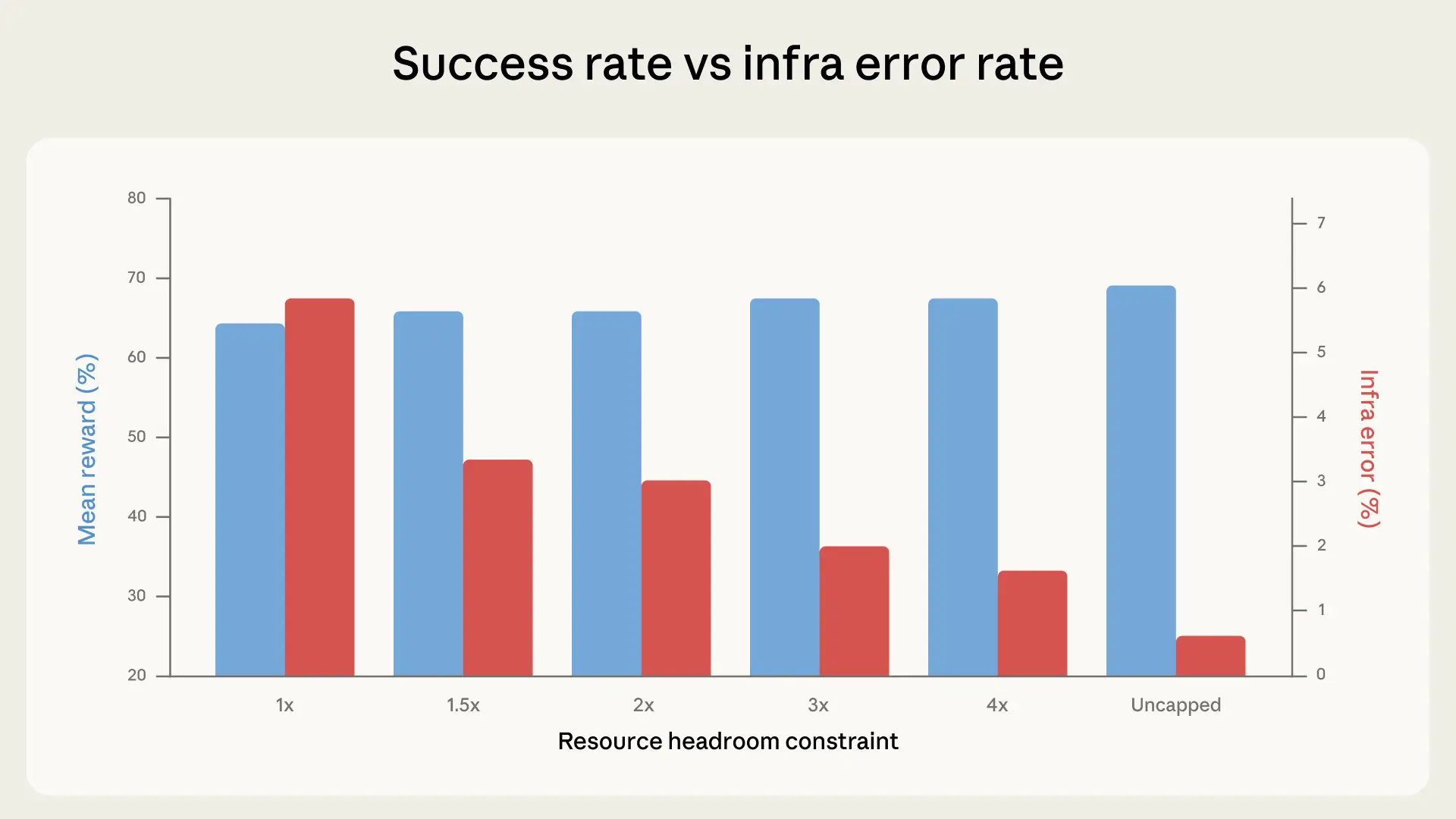

To quantify the effect of the scaffold, we ran Terminal-Bench 2.0 across six resource configurations, from strict enforcement of the per-task specs (1x), having them act as both floor and ceiling, to completely uncapped. Everything else stayed constant: same Claude model, same harness, same task set.

In our experiments, success rates increased with resource headroom. This was primarily driven by infra error rates dropping monotonically at each step, going from 5.8% at strict enforcement to 0.5% when uncapped. The drop between strict enforcement to 3x headroom (5.8% to 2.1%) was significant at p < 0.001. With more headroom, fewer containers get killed for exceeding their allocation.

From 1x through 3x, success scores fluctuate within the margins of noise (p=0.40). Most of the tasks that were crashing at 1x would have failed regardless—which is something that we observed in the data. The agent explores, hits a resource wall, and gets preempted, but it was never on a path to a correct solution.

Starting around 3x, however, this trend changes: success rates climb faster than infra errors decline.

Between 3x to uncapped, infra errors drop an additional 1.6 percentage points, while success jumps almost 4 percentage points. The extra resources enable the agent to try approaches that only work with generous allocations, such as pulling in large dependencies, spawning expensive subprocesses, and running memory-intensive test suites. At uncapped resources, the total lift over 1x is +6 percentage points (p < 0.01). At the margins, tasks like rstan-to-pystan and compile-compcert significantly improve their success rates when getting memory headroom.

How this affects measurement

Up to roughly 3x Terminal-Bench specs, the additional resources fix infrastructure reliability problems, namely transient resource spikes. The sandboxing provider used by the Terminal-Bench maintainers is implicitly doing this behind the scenes; the eval gets more stable without getting easier.

Above the 3x mark, however, additional resources start actively helping the agent solve problems it couldn't solve before, which shows that limits can actually change what the eval measures. Tight limits inadvertently reward very efficient strategies, while generous limits are more forgiving and reward agents that can better exploit all available resources.

An agent that writes lean, efficient code very fast will do well under tight constraints. An agent that brute-forces solutions with heavyweight tools will do well under generous ones. Both are legitimate things to test, but collapsing them into a single score without specifying the resource configuration makes the differences—and real-world generalizability—hard to interpret.

On bn-fit-modify, a Terminal-Bench task requiring Bayesian network fitting, some models’ first move is to install the standard Python data science stack: pandas, networkx, scikit-learn, and all their toolchain. Under generous limits, this works. Under tight ones, the pod runs out of memory during installation, before the agent writes a single line of solution code. A leaner strategy exists (implementing the math from scratch using only the standard library), and some models do default to it. Others don’t. Different models have different default approaches, and the resource configuration determines which of those approaches happen to succeed.We replicated the core finding across different Anthropic models. The direction of the effect was consistent, while the magnitude varied. The same trends seem to hold on models other than Claude, but we haven’t rigorously tested them.

We also tested whether this pattern holds on evals outside Terminal-Bench by running a crossover experiment on SWE-bench. We varied the total available RAM up to 5x the baseline across 227 problems with 10 samples each. The same effect held, though the magnitude was smaller: Scores again increased monotonically with RAM, but were only 1.54 percentage points higher at 5x than 1x. SWE-bench tasks are less resource-intensive, so a smaller effect is expected, but it shows resource allocation isn't neutral there either.

Other sources of variance

Resource allocation isn't the only hidden variable. In certain configurations, time limits too start playing a role.

In principle, every element of the evaluation setup can influence the final score, from the cluster health to the hardware specs, from the concurrency level to even egress bandwidth. Agentic evals are end-to-end system tests by construction, and any component of that system can act as a confounder. We have observed anecdotally, for instance, that pass rates fluctuate with time of day, likely because API latency varies with traffic patterns and incidents. We have not formally quantified this effect, but it illustrates a larger point: the boundary between "model capability" and "infrastructure behavior" is blurrier than a single benchmark score suggests. A model provider can shield its eval infrastructure from this by dedicating hardware, but external evaluators can't easily do the same.

Public benchmarks are typically meant to measure pure model capabilities, but in practice they risk conflating them with infrastructure quirks. Sometimes this may be desirable, as it enables end-to-end testing of the entire stack, but more often it's not. For coding evals meant to be shared publicly, running at multiple times and on multiple days would help average out the noise.

What we recommend

The ideal scenario is to run each eval under the exact same hardware conditions—both the scaffold running the eval and the inference stack—as it would ensure perfect reproducibility across the board. However, this may not always be practical.

Given how container runtimes actually enforce resources—via a guaranteed allocation and a separate hard kill threshold—we recommend that evals specify both parameters per task, not a single pinned value. A single exact spec sets the guaranteed allocation equal to the kill threshold, leaving zero margin: the transient memory spikes we documented at 1x are enough to destabilize the eval. Separating the two parameters lets you give containers enough breathing room to avoid spurious OOM kills, while still enforcing a hard ceiling that prevents score inflation.

The band between them should be calibrated so that scores at the floor and ceiling fall within noise of each other. For instance, in Terminal-Bench 2.0, a 3x ceiling over the per-task specs cut infra error rates by roughly two-thirds (5.8% to 2.1%, p < 0.001) while keeping the score lift modest and well within noise (p = 0.40). That's a reasonable tradeoff: the infrastructure confounder is largely neutralized without removing meaningful resource pressure. The exact multiplier will vary by benchmark and task distribution, and should thus be reported, but the empirical calibration principle is general.

Why we care

These findings have practical consequences beyond eval infrastructure. Benchmark scores are increasingly used as decision-making inputs, but this increased attention (and reliance) hasn’t always come with corresponding rigor in how they’re run or reported. As things stand today, a 2-point lead on a leaderboard might reflect a genuine capability difference, or it might reflect that one eval ran on beefier hardware, or even at a luckier time of day, or both. Without published (or standardized) setup configurations, it’s hard to tell from the outside unless interested parties go the extra mile to reproduce objective results under identical conditions.

For labs like Anthropic, the implication is that resource configuration for agentic evals should be treated as a first-class experimental variable, documented and controlled with the same rigor as prompt format or sampling temperature. For benchmark maintainers, publishing recommended resource specs (as Terminal-Bench 2.0 does) can go a long way, while specifying enforcement methodology would close the gap we identified. And for anyone consuming benchmark results, the core takeaway is that small score differences on agentic evals carry more uncertainty than the precision of the reported numbers suggests—especially as some confounders are simply too hard to control for.

Until resource methodology is standardized, our data suggests that leaderboard differences below 3 percentage points deserve skepticism until the eval configuration is documented and matched. The observed spread across the moderate range of resource configurations in Terminal-Bench is just below 2 percentage points. Naive binomial confidence intervals already span 1-2 percentage points; the infrastructure confounders we document here stack on top of that, not within it. At the extremes of the allocation range, the spread reaches 6.

A few-point lead might signal a real capability gap—or it might just be a bigger VM.

Acknowledgements

Written by Gian Segato. Special thanks to Nicholas Carlini, Jeremy Hadfield, Mike Merrill, and Alex Shaw for their contributions. This work reflects the collective efforts of several teams working on evaluations for coding agents. Interested candidates who would like to contribute are welcome to apply at anthropic.com/careers.